When 'cyber malls' were the future of shopping

Paying for purchases presented a problem

Back in 1995, it seemed the day was coming when consumers wouldn't have to set foot in a real-life shopping mall.

"It could be the biggest thing to hit the marketplace since the credit card," said host Peter Mansbridge on CBC's The National in March 1995.

"It" was an innovation in shopping made possible by the internet: "cyber malls" that meant online shoppers could "let their fingers do the shopping."

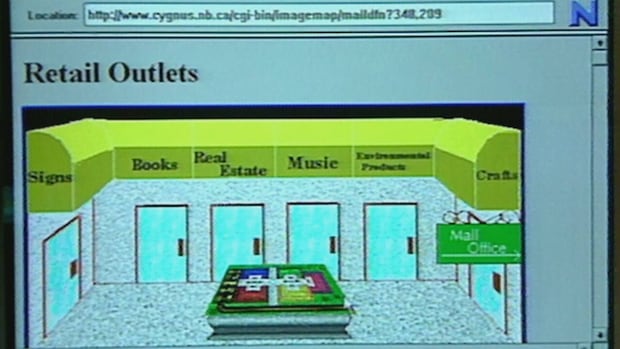

Reporter Ron Charles said a new kind of mall was "popping up on computer screens around the world."

Software to underwear

"These cyber malls exist on the internet, an international network of computers," explained Charles.

And internet users could buy "everything from software to underwear" without setting foot in a store.

But there was a hitch.

"To pay for something ... you have to send your credit-card number," said Charles.

Internet innovations

"That's simply not secure," said Jim Savory of the Consumers' Association of Canada. "Don't ever put anything on the internet you wouldn't put on a postcard."

Why not? As Charles put it, a credit card number had to bounce "from computer to computer to computer."

"Somewhere along the way, that card number could be intercepted," he said.

Two of the "world's biggest" companies, credit-card giant Visa and software maker Microsoft, had teamed up to come up with a way to make internet transactions safer.

Sian Owen of the Visa Canada Association estimated said internet transactions would soon reach $2 billion. Visa's goal was to find a way to "scramble" credit-card numbers.

Monuments for sale

In parallel, Charles said a Dutch company was working on something it called "e-cash" — "electronic money that only exists on your computer," said Charles.

"Shoppers transfer tokens from computerized accounts to businesses on the internet," he explained, showing something that could be bought that way: computer images of Canadian monuments.

But even with "easy, safe payment," retail analyst Mel Fruitman was skeptical the internet could play a big role in the international retail market Charles said was worth more than $1 trillion.

"You have to have the security in the product, in the vendor of the product," Fruitman said, viewing it as an obstacle if consumers "can't touch and feel the product."