Technology or natural solutions: what's our best bet for fighting climate change?

Some proposals to fight climate change sound like they’re straight out of science fiction

Humanity is currently facing some of its greatest challenges to date. We are witnessing debilitating droughts and ravaging wildfires, destructive floods and the loss of biodiversity — all things scientists have said for decades would happen due to our greenhouse gas emissions.

Apocalypse Plan B, a documentary from The Nature of Things, investigates some of the methods scientists are considering to slow down climate change, limit the damage that's already done and cool the planet.

Dimming the sun by adding more gas to the atmosphere

David Keith is a Canadian professor of applied physics at Harvard University. He's developed a strategy that could decrease the sun's impact on Earth in an effort to keep us cool.

It's based on the "volcano effect," which happens when large volcanic eruptions spew tonnes of polluting gases like sulphur into the atmosphere. Gas particles that make it high into the atmosphere actually block some of the sun's rays from reaching Earth's surface, creating a surprising cooling effect.

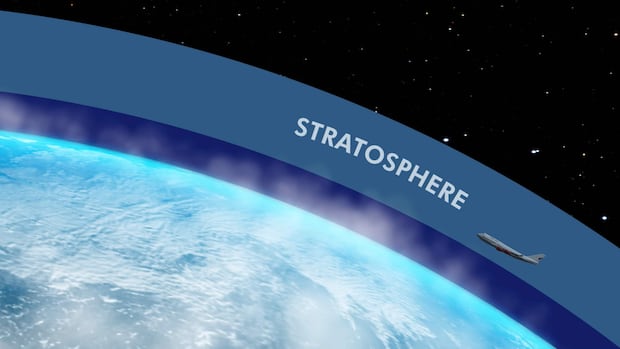

Keith's idea: intentionally release tonnes of sulphur gas into the stratosphere using aircraft. "It turns from a gas into little tiny particles, and those particles reflect away sunlight and can cool the planet a little bit," he says in the documentary.

This isn't a one-time fix. "We would have to start by putting 20,000 tonnes of sulphur in the stratosphere the first year," Keith says in a talk featured in the film. "After 50 years, we'd be putting a million tonnes a year of sulphur in the stratosphere."

Keith is quick to point out that this proposal only helps to cool the planet slightly while we still tackle the underlying problem of our emissions. "If anybody thinks this is a way to solve the problem of putting out CO2, they're insane," he says in the film.

Some scientists are worried by the idea. "We can see that [dimming the sun] actually disrupts plant productivity because you change the distribution of sunlight," says climate scientist Michael Mann. "That can end up shifting ocean currents and atmospheric wind patterns."

Brightening clouds using fleets of autonomous ships

Sarah Doherty, a senior research scientist with the University of Washington's department of atmospheric sciences, has her head in the clouds.

"Clouds are a really critical part of the climate system," she explains in the documentary. "One of the factors that controls the temperature of the planet is how much cloud cover we have."

Clouds work to reflect sunlight back out into space, and the whiter and brighter the clouds, the more sunlight is reflected. Doherty's found that the more cloud cover we have, particularly low cloud cover, the cooler our planet. She's been researching how we might brighten clouds over the oceans by using sea salt to enrich marine clouds.

In Australia, one team has put Doherty's theory to the test. "We showed that it's technically feasible to pump sea water and atomize it into trillions per second of tiny little sea water droplets," says Daniel Harrison, an oceanographer and engineer at Southern Cross University. They are interested to see how the technology could help the Great Barrier Reef, which has experienced numerous mass bleaching events in recent years due to warming oceans. "In theory, [those droplets] can go on to help brighten clouds and cool the reef."

But to brighten clouds on a large scale would take ships — a lot of ships — to make an impact. "You would need thousands," says Doherty. She envisions an autonomous fleet that would run on renewable energy, patrol specific ocean regions and respond to weather conditions.

Capturing carbon and storing it underground

Carbon capture is an attractive technology for the oil, gas, cement and steel industries, which are among the biggest emitters. It allows them to sequester much of the CO2 that's produced by their operations, compress and liquify it, and pump it underground instead of releasing it to the air.

"Carbon capture and sequestration is very seductive," says Mann. "[It] sounds like we can continue to burn fossil fuels and not worsen the climate crisis."

But he's quick to point out that there are still carbon emissions being released into the atmosphere. "In the very best cases, these plants capture maybe 70, maybe 80 per cent of the carbon pollution they generate."

So what can be done about the carbon that's accumulating in the atmosphere over time?

Direct air capture may offer a solution. This technology uses giant fans like a big vacuum, sucking up air and filtering out the CO2.

"We extract CO2 from the air and permanently remove it by storing it underground in rock formations," says Jan Wurzbacher of Climeworks, an Iceland-based carbon capture company that isn't associated with the fossil fuel industry.

Currently, their plant uses only green energy to remove an amount of carbon equivalent to what's emitted by 870 cars every year. But the company has ambitious plans to remove one gigatonne every year — just over the amount that humans emit every month — by 2050.

"It's not as invasive and dangerous as some of the other technologies that are being talked about," says Mann. "[But] you're trying to put the genie back in the bottle, and that's difficult to do."

Harnessing Earth's very own carbon capture technology: forests

The Earth has seen huge climate fluctuations over its 4.5 billion-year history. Over time, the climate stabilized, and the planet's animal and plant life began to recycle carbon in a balanced way.

One of the best examples of this all-natural carbon capture technology? Trees.

"I'd estimate that this tree stores about 5,000 kilograms of carbon," says Lola Fatoyinbo in the film as she examines just one tree in a forest. "That's five tonnes of carbon."

Fatoyinbo is a research scientist with NASA's biospheric sciences lab, and she studies forest ecosystems from space. In Fatoyinbo's research, she uses data gathered from instruments on the International Space Station to map the density of the world's forests, understanding their role in fighting climate change and how much CO2 they can remove from the atmosphere each year.

"Restoration of mangroves, forests and wetlands — these are really important mechanisms that are part of our fight," says Fatoyinbo.

Rethinking farming

Gabrielle Bastien holds up a single clump of soil. "[This clump] contains more microorganisms than there are humans on this Earth." Bastien is the founder of Regeneration Canada, part of a global movement among farmers to change how we grow our food.

"It's a whole ecosystem in there," she says in the documentary. Today's common farming practices, however, lead to soil degradation — one of the biggest contributors to climate change.

"Soils are actually the largest terrestrial carbon sink," says Bastien. "Aside from oceans, they contain the largest reserve of carbon on Earth." When that rich, biodiverse soil ecosystem is disrupted by plowing and tilling, its carbon content is largely emitted to the atmosphere.

In Apocalypse Plan B, Bastien visits Sebastien Angers, a farmer who is doing things a little differently. He's adopted regenerative farming practices that mimic nature, such as using a no-till drill to plant seeds and seeding a variety of crops in the same field so they can nourish each other. "If you think of a natural ecosystem, it's a very biodiverse system," he says.

Angers also uses cover crops to shade the soil. This helps keep the earth moist and cool, increases the diversity in his fields and reduces the need for pesticides.

"We need this richness," says Angers. "If you plow, you lose that. This field [took] 15 years to get this earthworm, fungi richness. It's really long to build, really easy to destroy."

But is it too late to affect change?

When it comes to fighting climate change, there appear to be many potential technological and natural tools in our arsenal, but how much time do we really have to use them?

"Because we've left it so late, we need to draw down as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as we can and turn it into solid carbon," says environmental writer and activist George Monbiot in the documentary. "The best, quickest and cheapest way of doing that is to turn it into trees, to turn it into wetlands, to turn it into other ecosystems."

"It really is not too late because social change can happen at great speed," he says. "We can change to being an ecological civilization, and we can change very rapidly indeed."