How a jazz drummer from Montreal is building a bustling farm business in rural N.B.

Heated greenhouses, meal box clients and appetite for good food are fuelling growth at Earth to Belly

On a quiet country road in Stanley, north of Fredericton, overlooking the densely forested Nashwaak Valley, is nestled an unassuming little farm where some bold moves are being made.

"Our idea when we first started was to be able to produce everything that a family would need for a year," said Louis St-Pierre, owner-operator of Earth to Belly Homestead.

Now, the 1½ acres he farms with his partner, Courtney Atyeo, both 31, and seven other employees are also producing enough vegetables, eggs, chicken, pork and baked goods to fill weekly meal boxes for 120 customers and make another few hundred sales in local stores.

St-Pierre would like to keep adding garden beds and growing his direct client base to between 3,000 and 4,000 within the next five or six years.

"I'm pretty confident with 10 to 15 acres in vegetable production we'd be able to do that," he said. "And two or three bigger greenhouses."

Selling directly means Earth to Belly doesn't have to settle for wholesale prices or supply the large quantities required for contracts with grocery store chains.

"It basically allows us to get maximum dollars for what we're selling," St-Pierre said.

It takes a pretty big crew to pull it off, including a driver who delivers the boxes by truck throughout the Nashwaak Valley, the Fredericton area and Saint John.

"It's a big logistical nightmare, but … it's a format that works for us," he said.

Earth to Belly started doing meal boxes two years ago with 15 customers. Last year, the farm supplied 80 customers for 16 weeks. This year, it's filling 120 boxes for 30 weeks and plans to keep the program going on an every-other-week schedule over the winter.

St-Pierre bought the 50-acre former Flying Shoe Farm property less than eight years ago and has been steadily building a profitable, modern small-scale farm business.

He and Atyeo have several fields in production, two greenhouses, a plant nursery, half a dozen chicken coops, a commercial kitchen, a vegetable washing and storage area and a pottery studio.

In one greenhouse, they grow cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, turmeric and ginger — which generate about 30 per cent of the farm's vegetable income, St-Pierre said.

The greenhouses and plant nursery are heated to some extent year round, which is costly, but increases the yields four fold, he said.

The heating, cooling and watering systems — for the plants and the animals — are all automatic and some have remote control by app.

Also helping to reduce St-Pierre's workload are two managers, one for the fields and one for the tomato greenhouse.

Field manager Adam Jeffrey is originally from the area, but has experience farming in B.C.

Finding workers is tough, Jeffrey said.

"Consumers have to recognize the value of this kind of farming in order to support living wages on the farm," he said.

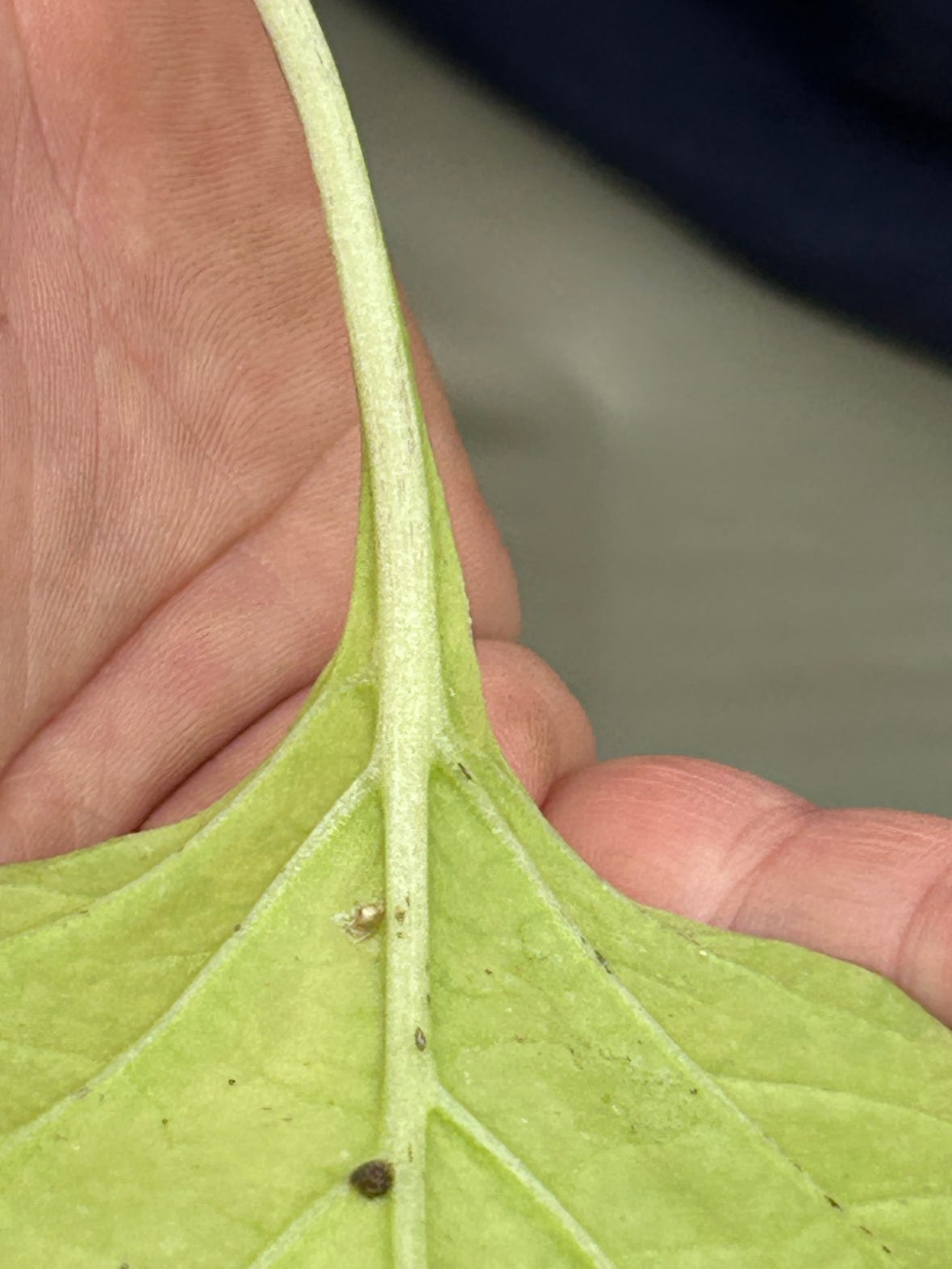

Instead of pesticide, Earth to Belly uses nets in the fields and predatory insects in the greenhouse.

For fertilizer, they use pelleted chicken manure and their own compost.

Jeffrey is working to create a bio-complete compost so that eventually they won't have to till.

Fertilizer is applied in the greenhouse weekly instead of the "old school" method of front loading at the start of the season.

It's a little more work, but gives the plants what they need to bear a lot of fruit, St-Pierre said.

"A commercial conventional farm gets about a fifth to a tenth the production we get per square foot," he said.

That calculation is based on getting two or three crops per season and fitting five or six rows in the space that would be required for one row on a farm that uses a tractor, he explained.

Last year, 18.6 kilograms of cherry tomatoes were harvested per square metre in the greenhouse, added St-Pierre.

By virtue of not using tractors, artificial fertilizers, pesticides or fungicides, they've also avoided recent cost increases.

Five years ago, their prices were 30 to 40 per cent higher than grocery store alternatives, said St-Pierre. Now, they're equal or below.

Farm boxes are selling for $135/week.

'Huge' market opportunity

It's a great time to get into small-scale farming, in St-Pierre's view.

"The market is booming, and it's going to be expanding over the next few years," he said.

"There's not enough food being produced in New Brunswick. If you are able to bring a good quality product to market, there will be people to buy it."

But farming is not for everyone, he warned.

For starters, St-Pierre estimates it would take $150,000 to $200,000 plus the cost of land.

Renting might be a better option for starting out, he suggested.

It also takes business and science know-how.

He spends about 20 hours a week on marketing, advertising, looking at reports and making sure money is well spent.

When it comes to things like crop yields, density and plant pathology, St-Pierre reads a lot, experiments and consults outside experts weekly.

"Awesome" resources are available through the government, he said.

Even armed with knowledge, you still have to be willing to take risks, said St-Pierre, who is well-practiced in the art.

It was quite a leap to reinvent himself as a rural New Brunswick farmer after growing up in the suburbs of Montreal, studying music and working as a touring musician.

The transformation began when he spent a couple of months between gigs living "on frogs and squirrels" in his father's woodlot.

He got to Stanley via a posting on the World Wide Work on Organic Farms website (wwoof.net) and within a couple of years he had taken over the farm.

St-Pierre and Atyeo lived in a tiny home while the business got going, "roughing it" with an outhouse, supplementing their diet with hunting and gardening and selling eggs to pay for fuel and other things.

Today, they can live more comfortably in a regular sized house with their two-year-old child, close to nature and extended family.

Carving out personal time is essential, said St-Pierre, who has seen some of his farming friends burn out.

It's all feasible, he said. "You just have to plan it."