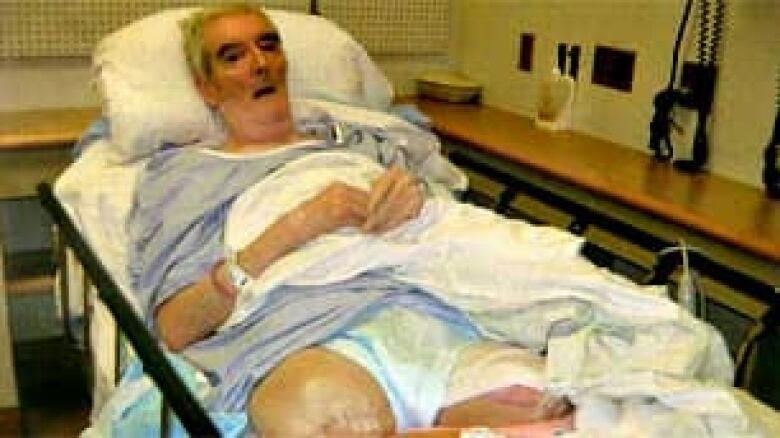

Senior loses legs to hospital infections, bedsores

Family blames neglect by staff for double amputation

The daughter of a retired B.C. man who died in a publicly funded, long-term care facility believes her father suffered needlessly as a result of neglect by staff.

"What they did was wrong," said Rita McDonnell. "The care was awful."

Gary Davis, a former postal carrier from Surrey, was 68 years old when he developed severe bedsores and hospital-acquired infections, under the care of the Fraser Health Authority. He eventually had to have his legs amputated as a result.

"It makes me sick to my stomach," said his daughter. "I still think about it. I can't sleep some nights because I think of what it was like for him."

'It was awful … he was rotting.' —Daughter Rita McDonnell

Records shows staff at three facilities failed to keep Davis off his back — despite doctor's orders — as his bedsores and infections became increasingly worse.

"In order for [his sores] to get as severe as they did, he had to be sitting on his back so long — in his own urine, feces, you name it," said McDonnell.

"They admitted to us that they should have turned him more often," said her husband Mark McDonnell. "They didn't give him the care that he deserved."

Patient not mobilized enough

Davis' health downturn began when he was admitted to hospital in 2006, with a groin aneurysm. Over the next several months, he suffered from poor circulation and other complications, in Langley Memorial and Royal Columbian Hospitals.

A summary of Davis' medical records from that period show "the patient has been transferred to the wheelchair .… However, this has not been done consistently."

"Nurses notes lack information as to how frequently the patient was mobilized."

The notes show he developed pressure ulcers — commonly known as bedsores — on his back and legs and state that the "wounds continued to deteriorate, and he contracted e-coli in the urine and a staph infection."

Fraser Health's director of residential services, Heather Cook, said Davis' poor circulation was also a complicating factor.

"When you have poor circulation, it really challenges the ability to heal," said Cook. "This was an individual with exceedingly complex medical conditions."

On at least two occasions, doctors ordered Davis be kept off his back as much as possible. However, McDonnell was not informed about his dad's sores, records show, until several months after they surfaced.

"I started asking questions," said McDonnell. "I wanted to know why he smelled so bad."

McDonnell said she was horrified when staff removed his bandages and she saw the large, open, festering wound on her father's lower back for the first time.

"It was awful, unbelievable," she said. "It was black. He was rotting."

When she then complained her father wasn't being moved enough, McDonnell said, "One of the nurses told me, 'Care aides don't get paid enough, you couldn't pay me enough to do that job'."

Davis was transferred to Cedar Hill, a long-term care facility adjacent to Langley Memorial Hospital, where the records indicate staff also didn't move him as much as recommended by the specialists.

Specialist expressed alarm

"The wound care specialist … mentioned that the patient was in bed a lot," the file notes state. "He has not been taken out of bed … wounds were still not healing"

McDonnell said that same wound specialist pulled her aside and suggested she consider suing the health authority.

"She said you should get a lawyer for what happened to your dad — the care has been horrific."

According to the file notes, "Staff at Cedar Hill did have some difficulties when trying to mobilize the patient and tend to his wounds. The staff were educated on how to properly mobilize the patient."

The facility did provide a special air mattress, to relieve the pressure, but the notes indicate staff didn't use it properly, which negated its effectiveness.

"They let him lie there — and they kind of gave up on him a bit," said his son-in-law.

The couple insisted they couldn't bring Davis home, despite their concerns, because he was too ill for them to look after.

Several weeks later, McDonnell was told that if her father's legs were not amputated, he would die from the spreading infection — so the family consented to the operation.

"In order for his back to survive, he had to lose his legs, because of the sores on his legs, the bedsores on his legs," said McDonnell.

Without his legs, Davis recovered and lived infection-free for several more months.

Review finds several care concerns

Soon afterward, Davis died — while still in the long-term care facility. His family was told he succumbed to pneumonia.

"His quality of life was pretty severe. He said, 'I can't go to the washroom on my own. This hurts. I can't be human. I don't feel human.' It was awful for him," said McDonnell.

"I miss talking to him and visiting him. He was important to me," she said tearfully.

Meantime, a national group trying to raise awareness about pressure ulcers said cases like his are all too common.

"It is a huge problem," said Pat Coutts, a wound care specialist and chair of the Canadian Association of Wound Care. It estimates 70 per cent of bedsores in Canadian hospitals could have been prevented.

Most bedsores can be prevented, group says

"The skin is an organ. It needs to be looked after," Coutts said. In a facility, patients need to be turned, or be on a surface that will turn them. If they're in diapers they need to stay as clean and dry as you can possibly keep them."

Submit your story ideas:

- Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC TV, radio and the web.

- We expose waste, incompetence and wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

- We want to hear from people across the country with stories they want to make public.

The government review into the Davis case criticized Fraser Health for not informing McDonnell about what was going on with her father.

It also expressed concern about his care being "fragmented," and it concluded, "Assignment of a primary care physician might have provided a more consistent continuum of care."

Cook from Fraser Health insisted lack of communication with the family was the biggest problem.

"With an individual, with the complex medical issues that this particular resident had, the likelihood was that there was very little we could have done to impact his life anyways," said Cook.

"Had we been able to communicate more effectively and in more timely fashion with the family, this might not have been so challenging for them."

That doesn't satisfy McDonnell.

"It's nice and fancy for them to say that," she said. "It's their way of getting out of what really happened. They didn't do their job."

As a result of the Davis case, Cook indicated Fraser Health has improved its communications with families and put in a better system to care for patients who are transferred between facilities.

The Canadian Association of Wound Care, which gets funding from the industry that supplies hospitals with wound care equipment, estimates 25 per cent of people in Canadian health-care facilities have a pressure ulcer at any given time.

Fraser Health disputes that figure, saying less than three per cent of long-term care patients develop the sores, while in any of its facilities.

McDonnell now hopes her father's story will encourage other families be more vigilant — to watch for a problem she was previously unaware of.

"I just want people to be aware of what can happen to them and their loved ones," she said.