Imaging reveals 2,000-year-old ice mummy's 'incredibly impressive' tattoos

Forearm sleeve of big cats hunting is 'masterpiece,’ says artist who studied ancient ink

More than two millennia ago, a woman sat for hours on end in the ancient grasslands of a Siberian mountain range to have her body adorned with elaborate tattoos of creatures both real and mythical.

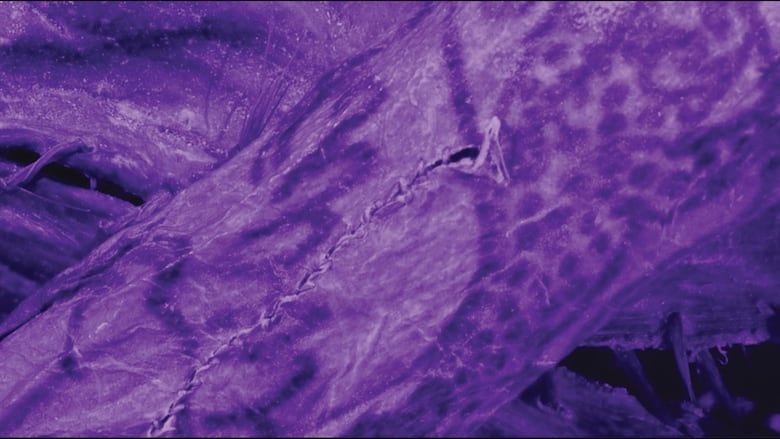

When she died, her body was preserved under the permafrost for thousands of years, but her tattoos faded and became invisible to the naked eye.

Now researchers have used high-resolution, near-infrared photography to bring those ancient tattoos back to life and worked with modern tattoo artists to shed light on the tools and techniques that made them possible to begin with.

"These tattoos are incredibly impressive," Daniel Riday, a traditional tattoo artist from Les Eyzies, France, who worked on the research, told As It Happens guest host Rebecca Zandbergen. "This kind of research is almost a direct window into the past ... and it's very humbling to really be so close to the roots of this practice."

The findings are published in the journal Antiquity.

'A very technical skill'

Tattooing is a long-standing practice in many cultures around the world, with the oldest known tattoos dating back 5,300 years to Ötzi the Iceman, a prehistoric hunter whose tattoo-clad remains were found preserved in glaciers in the Italian Alps in 1991.

But it's a difficult field to study because preserved tattoos on human flesh, like Ötzi's, are exceedingly rare.

For this study, researchers looked at the remains of a 50-year-old woman from the Pazyryk culture, Iron Age pastoral people who lived in the Altai Mountains of Central and East Asia. She's one of several Pazyryk ice mummies whose remains were found preserved inside the mountain's ice tombs in the 19th century.

Scientists have long known that the Pazyryk mummies were tattooed, but it was impossible to study the faded images in real detail.

"Prior scholarship focused primarily on the stylistic and symbolic dimensions of these tattoos, with data derived largely from hand-drawn reconstructions," Gino Caspari, an archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland and the study's senior author, said in a press release.

But three-dimensional scans of the Pazyryk woman's tattoos have revealed them in stunning detail.

On her thumb sits a rooster with swirling tail-feathers. Her left arm bears a mythical griffon attacking a large stag, while an elaborate scene of leopards and tigers hunting two deer with intricate antlers is on her right forearm.

The latter, Riday said, is particularly impressive and likely would have taken two sessions of four or five hours each to complete.

"It's graphic, it's well placed, it's imaginative. It's really a masterpiece," he said. "We think that the left arm was done by an artist of less skill, or maybe the same artist earlier in their career."

The tattoos appear to have been done using a stick-and-poke technique, Riday said, which means someone used ink-dipped needles to create the images one single dot at a time.

The researchers suspect that small clusters of either thorns, or iron or bronze needles, dipped in a pigment of soot and animal fat were used.

It suggests, he said, the work of a true professional.

"It's a very technical skill to create these kinds of tattoos, especially so long ago," Riday said. "The person doing the tattoos would need to know what they're doing and how to do it safely, and be able to create this sensational imagery that we're seeing. It takes time and skill."

Anthropologist and archaeologist Andrew Gillreath-Brown, who was not involved with the study, said this use of high-resolution imaging to get a closer look at ancient tattoos is "pretty exciting" and one he hopes will open up new opportunities.

Gillreath-Brown, who once identified and researched a 2,000-year-old tattooing needle from the Native American Pueblo peoples, commended the researchers for looking beyond the broader cultural significance of tattoos, as others have, and instead focusing on the artistry and technique behind them.

"Being able to move outside of just even the person being tattooed themselves was really quite remarkable and will, I think, take things in a whole new direction," Gillreath-Brown, manager of the Yale Center for Geospatial Solutions in New Haven, Conn., told CBC.

Riday, a stick-and-poke artist, himself, said he's currently working to recreate a tattoo needle in the style of the Pazyryk so he can tattoo one of the woman's pieces onto his own body and learn more about the ancient technique.

He said it's been amazing to connect with the deep history of his chosen profession.

"It's very richly satisfying," he said. "The chance that this individual was preserved through the ages in a burial tomb below the permafrost in Siberia, and scientists were able to find this tattoo and make it known to the world that it exists, it is really just remarkable."

Interview with Daniel Riday produced by Livia Dyring