What eating insects in Mexico taught this Montrealer about food systems

'Bugs [are] the food of the future,' says author Taras Grescoe

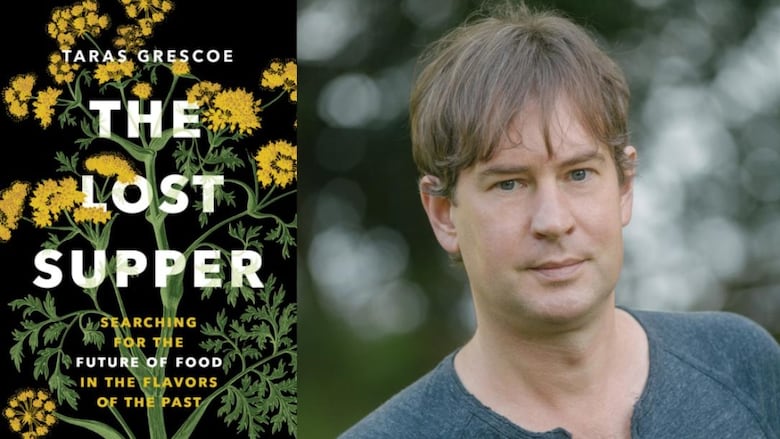

Dismayed by the state of today's food systems, Montreal author Taras Grescoe travelled the world to dig into the agricultural practices of the past.

One of the locations he went to was Mexico City, where the diverse options within the country's edible insect culture convinced him that "bugs [are] the food of the future."

"Intellectually, it makes a lot of sense," he told The Current's Matt Galloway. "It was only when I went down to Mexico City that I was kind of convinced on the flavour side."

Grescoe documented his travels and findings in the new book, The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavours of the Past.

He spoke with Galloway about the insect cuisine he had in Mexico — and what the past can teach us about today's food systems. Here's part of their conversation.

Part of this book, which is fascinating, is travelling back in time. But how did we end up at a place where our choices have been narrowed so much?

We've had sort of three major agricultural revolutions. There was the neolithic revolution which, going back 10,000 years ago we all became settled agriculturalists living in more or less urban cities settings with, you know, a rural hinterland supplying the cities. That really limited diversity. Before, we were drawing from all these different food webs as hunter-gatherers or foragers or pastoralists.

Then there was the industrial agricultural revolution, where you're bringing in all these different breeds of animals. There's sort of scientific hybridisation. We're getting far more efficient at feeding far more people.

Then there's the green revolution, which really kicked things into overdrive starting in the 1960s, where you're bringing the power of fossil fuels along with fertilizers, along with new breeds of wheat that can feed the millions and the billions. And along with that, we're seeing a big increase in population.

So those three revolutions sort of brought us to where we are today, and a lot of people are saying it's time to tap the brakes, that the food system is broken.

Agriculture is important, we're just doing it wrong. And in the book I kind of go back and find examples of ancient lost foods that people are bringing back to life now, and those are exciting stories for me.

Why was the past in particular the place that you thought those answers would live?

I think we're seeing an even greater narrowing of diversity, the way things are going. A lot of people are calling for lab-grown meat.

If you look at hunter gatherers, they were eating an incredible ... range of foods — and we've lost that, so the past is definitely the place to go.

What I'm really interested in is the intensity of flavour. That was the one of the big discovers when I was doing this book, the fact that a lot of the food that we ate before really brought this intensity of aroma and flavour, just sensual experience.

As far as I know, you don't have a time machine, but what you do have is access to travel and places where there are still practices going on that draw on the past.... Tell me about what you learned in Mexico City.

Well, I started off with the whole idea that bugs — edible insects — are the food of the future, and I was intrigued by this idea, and a little repulsed.

I'm a pretty adventurous eater. Like, I've gone to Thailand and eaten grubs on the street, that kind of thing. We have an event here in Montreal, the Insectarium, where they do bug tastings and things like that. So I'm not averse to it, but I've never found a way to really work them into my diet.

I went down to Mexico City because they have a really, really venerable tradition of entomophagy [the eating of insects] ... and the interesting thing is it's in really high-end restaurants.

So I was searching for … the eggs of the water boatmen. These are these little creatures that sort of scuttle on the surface of lakes, lakes which are disappearing from Mexico City area.

I did manage to track it down, and it was delicious. But what I found even more interesting was just the things like escamoles, which are the eggs of flying ants, which are some of the most expensive things you can find in restaurants there.

I was actually seduced by the edible insect culture of Mexico City desert. I sort of really got into it. I was like, what am I going to seek out next?

Maguey worms served with guacamole and homemade tortillas at one of the best restaurants in Mexico City. So I was actively seeking them out.

But when I got back home to Canada, the issue was trying to convince my kids, Desmond and Victor ... to follow their crazy dad and incorporating bugs into their diet. I was a lot less successful with that.

So bugs [are] the food of the future. I can see the case for it.… On the other hand, incorporating them into our day-to day lives, I'm not so sure. I think we can turn to other foods, but that's sort of one of the big picture arcs of the book.

WATCH: People react to tasting insect delicacies

Your kids are a huge part of this book. Are they onside with this kind of experiment, the bugs and the garum [an ancient Roman fish sauce] and other things?

Victor, just seven years old, completely neo-phobic. He's drawn a line in the sand. He's not gonna eat any of this stuff. His brother Desmond, however, followed me to the largest cricket farm in the world, which is near Peterborough, Ont., and he became a convert there.

So he regularly puts chapulines, which are sort of lime-toasted crickets, into his tortilla [and] into his burritos. He's always been into relatively extreme foods like kalamata olives and capers, that kind of thing.

He's not a problem. He's on board. Victor, he's a work in progress. We're going to keep on working on him.

Q&A edited for length and clarity. Produced by Amanda Grant