She kept quiet for years. Now this doctor is talking about her own disability

Originally published on Nov. 18, 2017

Last November, a Canadian medical team achieved a first: Successfully performing in-utero surgery to repair a fetus with spina bifida, an operation that had never been done in this country before.

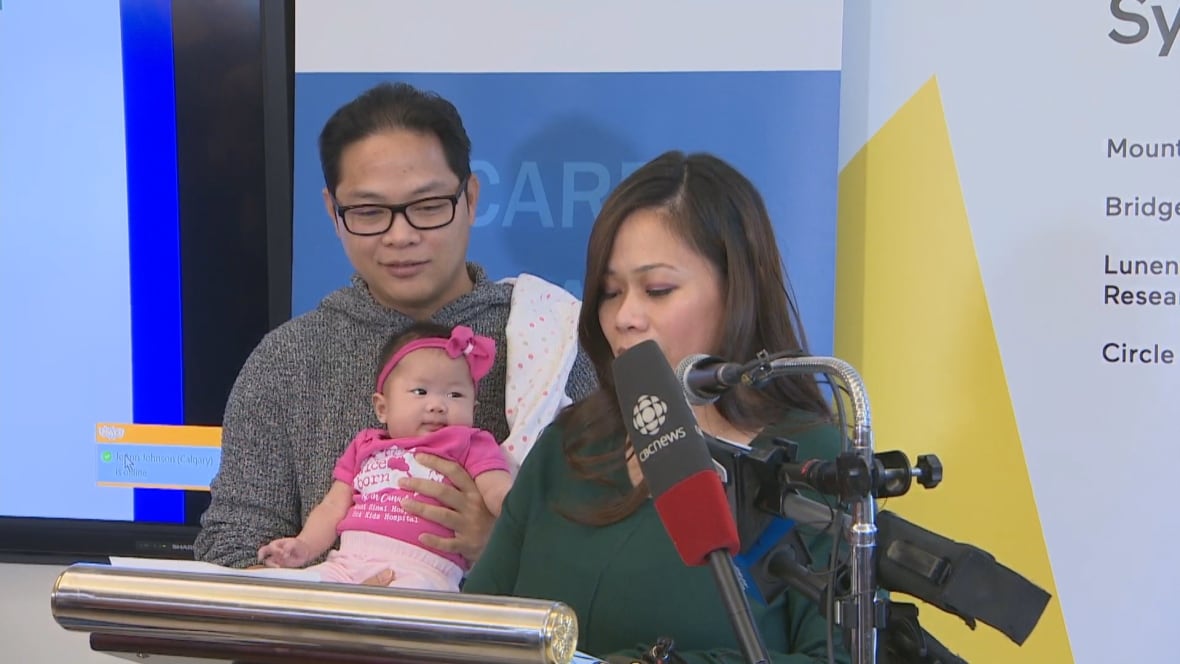

The birth defect can lead to lifelong disability. The baby they operated on, Eiko Crisostomo, is now almost a year old, and thriving, according to a recent report from her mother.

But surgeons weren't the only ones providing care to the baby and her family. Dr. Paige Church, the director of the Neonatal Follow-Up Clinic at Toronto's Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre counselled the baby's parents on what to expect from their newborn and her condition.

It's a role for which she's uniquely suited. In addition to her role at Sunnybrook, she's a developmental pediatrician in the spina bifida program at Toronto's Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

But what many of her colleagues and patients didn't know until recently was that Dr. Church also has spina bifida.

They were unaware because for years, she hid her condition, fearing that it might be seen as a weakness in what she describes as a "medical culture that is not very forgiving of our own colleagues having any issues."

"I had wanted to be a doctor my whole life, so the last thing I wanted was for this to get in the way of that,' she told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of White Coat, Black Art.

I had wanted to be a doctor my whole life, so the last thing is wanting to have this get in the way of that.- Dr. Paige Church, who has spina bifida

"I think in medicine we're taught it's not about us and if it isn't about us, then you have to start covering up."

Her coverup, which she called "exhausting and isolating" began in medical school and continued into her residency and to her current job. It was a "very well-hidden secret," she says.

She told Dr. Goldman that her form of spina bifida causes weakness in her legs and requires her to use a catheter to relieve herself six or seven times a day.

At work she would limit what she ate and drank to avoid trips to the washroom, getting by on 12 crackers a day so she could see patients without constant interruptions to relieve herself. At night, she spends an hour-and-a-half flushing out her bowels with a saline solution.

"I think people thought I was hyperactive," she said. "I would get up in the middle of a meeting because I had to use the washroom, but I would pretend my phone rang or my pager went off."

She says she felt she had no choice at the time.

"You're supposed to be able to do it all and run to the emergency room like they do on TV."

Time to go public

But last month, Dr. Church revealed her complications with spina bifida, in an op-ed in an issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

She says the decision was related to the fact that she was struggling with medical training that taught her to be objective and dispassionate when counselling patients. She now believes her disability and her work with kids who have spina bifida can inform that work.

"I started to realize I didn't necessarily know what the recipe was supposed to be. For one family, one condition might mean something, and for another it might mean something totally different, even though the condition is the same condition."

She's still working on finding a balance but is now more open with her young patients.

"I don't know if I have an answer yet ... With my children in spina bifida clinic, I have tried to be more open and forthcoming [about my experience], in the hopes it can minimize some of the stigma they are experiencing."

She's also hoping that being more open might help her colleagues see that when it comes to disability, "there is a spectrum and that we're all sort of moving around on it."

I would love to see that there isn't such a stark divide between typical or normal and disabled ... It's a spectrum, and we're all on it.- Dr. Paige Church

"That variety is exactly what we want in life. That's what makes culture rich and interesting," she says.

The pediatrician is thrilled the breakthrough surgery performed in Toronto will offer hope and options to parents.

"I'm excited for us. For counselling, it offers something that has hope in it. To be able to tell parents this intervention is going to minimize surgical needs later, that's huge."

At the same time, she wants them to understand that having a disability doesn't define a child. In her case, it enhanced who she became as an adult, far beyond what her medical record says.

"[It doesn't say] I'm a mom. I have an amazing child. That I am a doctor. That I am a wife. That I'm a daughter and I have two incredible parents and incredible friends. This condition has given me all of that. It's the good and bad. It's given all of it to me. Without it, I wouldn't be who I am."