Search for B.C.'s Best Symbol: Coastal Championship

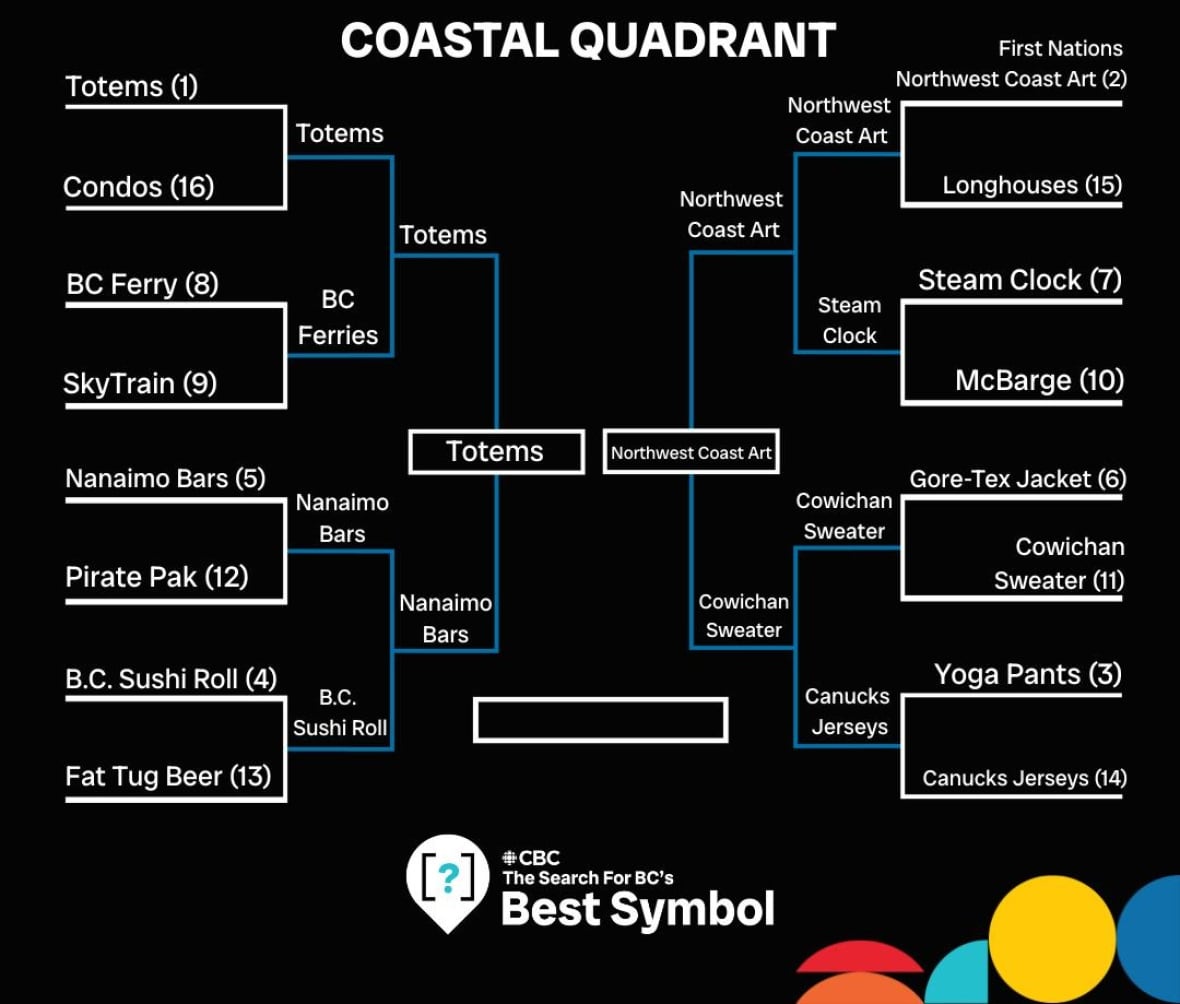

It's Totem Poles versus Northwest Coast Art in our 3rd quarterfinal matchup

Xwalacktun, a sculptor and carver from the Squamish and 'Namgis nations, holds up his drum and shows all the details of the piece of art that adorns it.

"There's movement happening," he says, pointing to the thunderbird in the middle and the series of small circles surrounded by crescents.

"If you were to throw a pebble into the water, it ripples. Triangles are a reminder that we're being watched, like the end of the eyelids … everything is connected here."

The trigons and ovoids are used to draw, paint, weave and carve depictions of creatures and nature in all types of Coast Salish art.

While showcasing symbols of nature, the works of art have, over time, become symbols unto themselves.

"When we do our artwork, we think of what's happened in the past, in the future, and what's happening now."

Symbols, but also 'artificial constructs'

Coast Salish art is often included within the genre of "northwest coast art," a catch-all way to describe commonalities between artwork created by different First Nations along the Alaska, British Columbia and Washington coasts.

But as Museum of Anthropology curator Jordan Wilson notes, terms like "Northwest Coast Art" or "Totem Poles" were colonial impositions: the northwest coast spans dozens of different First Nations. The word totem comes from the Ojibwe language, from the Anishinaabe people who historically resided near the Great Lakes, thousands of kilometres away.

"It's like this artificial construct," he said.

"They connect to a history of anthropology, a history of northwest coast art history, but then also a history of tourism and the construction of a distinctive Canadian and British Columbian identity."

It makes it ironic — and perhaps controversial, depending on your perspective — that after tens of thousands of votes, these two symbols remain as the two coastal finalists in The Search for B.C.'s Best Symbol.

Only one will move on to the semifinals next week. But at their core, Wilson hopes people remember where these symbols came from and originally reflected.

"These abstract, beautiful objects that can be admired," he said, "while losing sight of the fact that they're very much connected to our political lives, our social lives and ceremonial lives."