Canada's weird liquor laws

Radio host Terry David Mulligan’s decision to stroll across the B.C. border to Alberta with a case of wine on May 13 was meant to draw attention to an old, and in his mind, outdated law governing alcohol in this country.

The B.C. radio host's beef is with Canada’s Importation of Intoxicating Liquors Act, a 1928 law that states "no person shall import, send, take or transport, or cause to be imported, sent, taken or transported, into any province from or out of any place within or outside Canada any intoxicating liquor."

The only way you can legally move a bottle of wine from one province to another — or from another country into Canada — is with the permission of the provincial liquor control board. Mulligan contends that this is an inconvenience to consumers and a hindrance to winemakers hoping to expand their customer base.

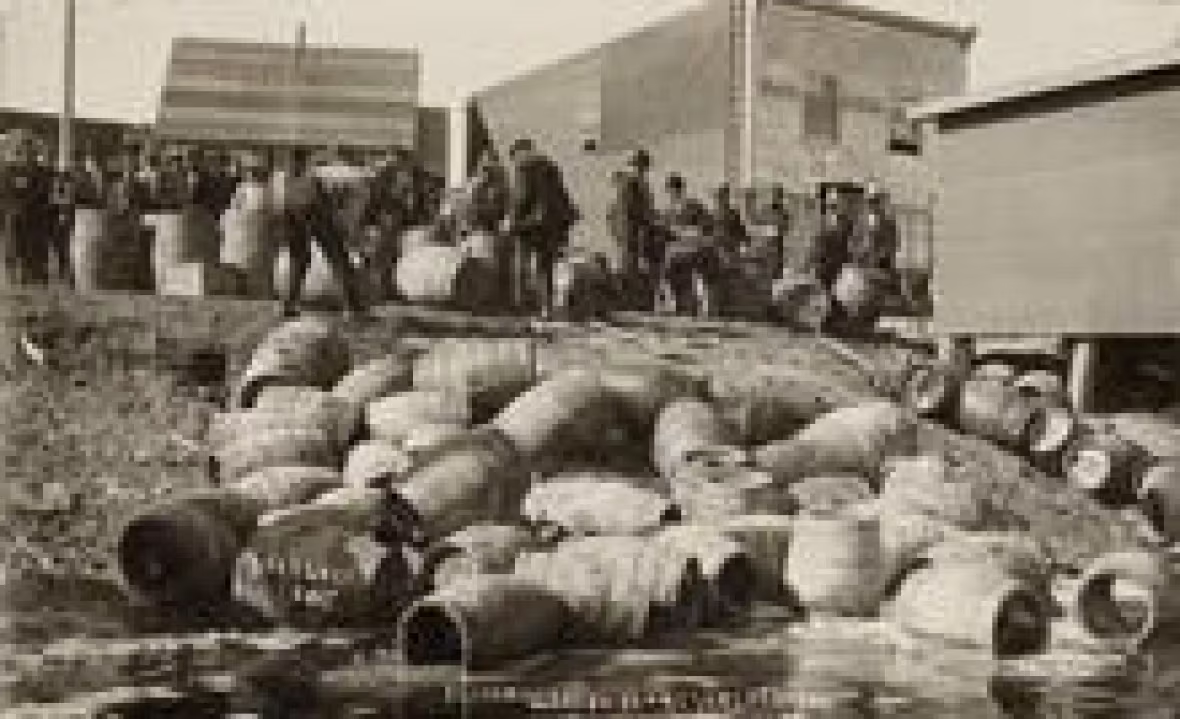

The law is a reminder of the legacy of Prohibition, a temperance movement that broke out across Canada and the U.S. in the early 20th century.

'You can’t understand any North American liquor laws unless you trace them back to Prohibition.' — Wine lawyer Mark Hicken

The Canadian law regarding the shipping of alcohol was meant to thwart bootleggers, and led to a gradual devolution of federal responsibility to the provinces in matters relating to liquor. Each province established an agency that oversees the distribution, sale and consumption of wine, beer and spirits.

"A lawyer down in California once said to me, ‘You can’t understand any North American liquor laws unless you trace them back to Prohibition,’" says Mark Hicken, a wine lawyer and advocate in Vancouver.

"You look at any regulatory structure in North America and if it was examined in a global perspective, you’d look at it in stunned disbelief, like ‘What is going on here?’ It really does go back to the Prohibition mentality of control, and the slow loosening of control over the years."

The original mandate of the alcohol shipping law was a moral one, Hicken says, but it has evolved into a financial consideration.

"The shipping laws were brought in to stop the inter-provincial bootlegging traffic following the repeal of Prohibition at different times and in different provinces," says Hicken. "Today, the major reason for the continuation of those laws is money – the liquor boards want to maintain absolute control over all liquor in their jurisdiction so they can levy a liquor board markup on it."

Because the provinces make their own laws, there are discrepancies from region to region.

Quebec, for example, has always taken a more laissez-faire attitude to alcohol. It was the only jurisdiction in Canada or the U.S. that did not impose complete Prohibition and it remains more relaxed on two key issues. The first is the age of consent — in Quebec (as well as in Manitoba and Alberta), the legal drinking age is 18. The other is the general availability of booze.

"Depending on where you are [in Canada], the retail market is different," says André Fortin, director of public affairs at the Brewers Association of Canada.

"In Quebec, you can buy beer in corner stores and grocery stores, whereas in Ontario you can only buy it at the Beer Store and the Liquor Control Board of Ontario. And you have other provinces like Alberta, which offers a private retailer market, you’ve got some mixed markets in British Columbia, you’ve got some government-only markets like New Brunswick, P.E.I., Nova Scotia."

There are also differences in the concept of bringing your own wine to restaurants. Currently, in Alberta, Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, restaurants can apply for a liquor permit that will allow them to serve wine that customers bring in themselves. (The restaurants charge a so-called corkage fee for this function.)

Last year, the Quebec Brewers Association lobbied the provincial government to give the same consideration to beer.

B.C. doesn’t allow this service, but it recently changed its law so that restaurant customers who didn’t finish a bottle of wine could take it home with them.

But there were conditions.

"The rule is that the restaurant has to re-seal it for you, and it’s supposed to be in the back seat or trunk of the car," says Hicken. "I think it’s a good compromise."