The Black Londoners Project uncovers lost histories of freedom seekers who settled here

Their life stories can be traced on an interactive map of London

Researchers at Western University have been working since 2023 to trace the histories of Black freedom seekers who came to London after escaping enslavement. Now they've launched an online map and database to share these stories with the public.

"I think the whole project itself has been a large positive for me," Ronique Gillis, one of the research assistants working on the project, said. "I'm getting to learn a lot about the Black community that I did not know even existed in London."

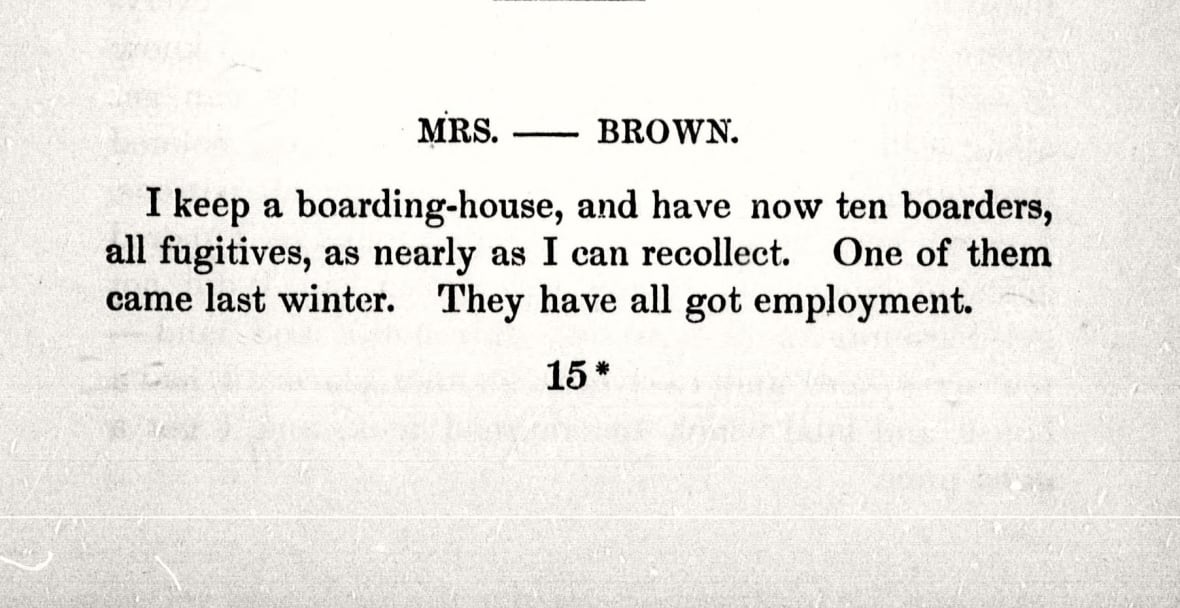

Somewhere around 1855, a formerly enslaved woman living in London, referred to only as Mrs. Brown, shared her story with Benjamin Drew, a white abolitionist author from Boston. Her account was only three sentences long:

"I keep a boarding-house, and have now ten boarders, all fugitives, as nearly as I can recollect. One of them came last winter. They have all got employment."

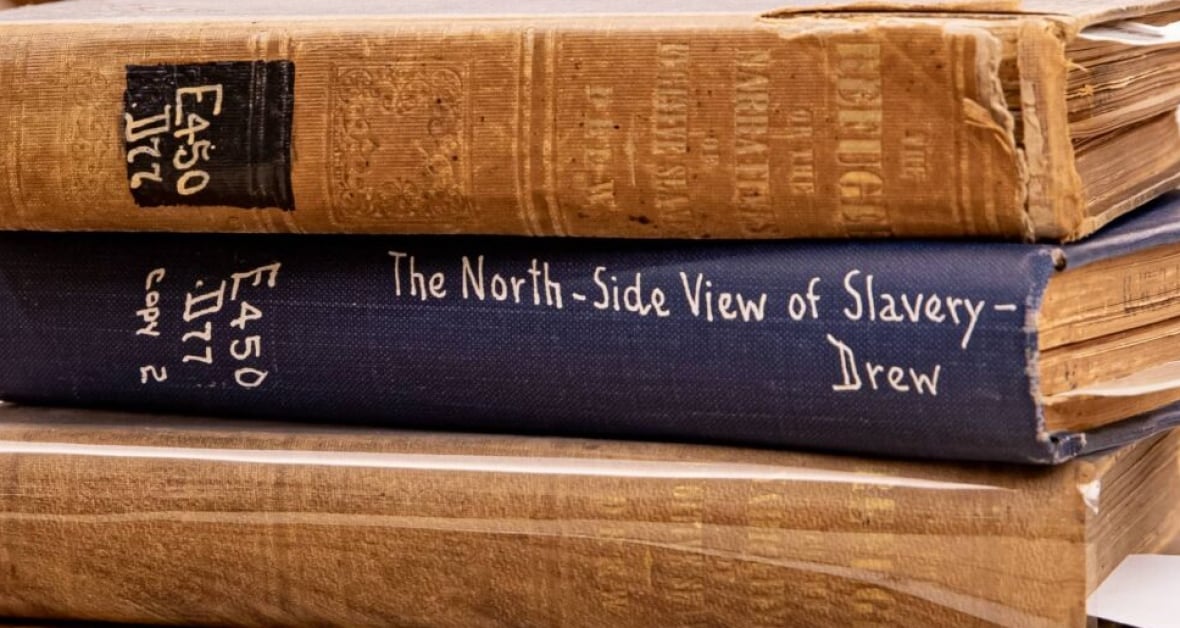

She's among the stories of 16 formerly enslaved people who'd fled to London were included in Drew's book, A North-Side View of Slavery. While at first glance, these accounts give only a fleeting glimpse into the lives of the freedom seekers who lived here, The Black Londoners Project was able to use this information as a starting point. With the help of historical archives, censuses and other available records, the research team has been able to uncover details of their lives that were previously buried.

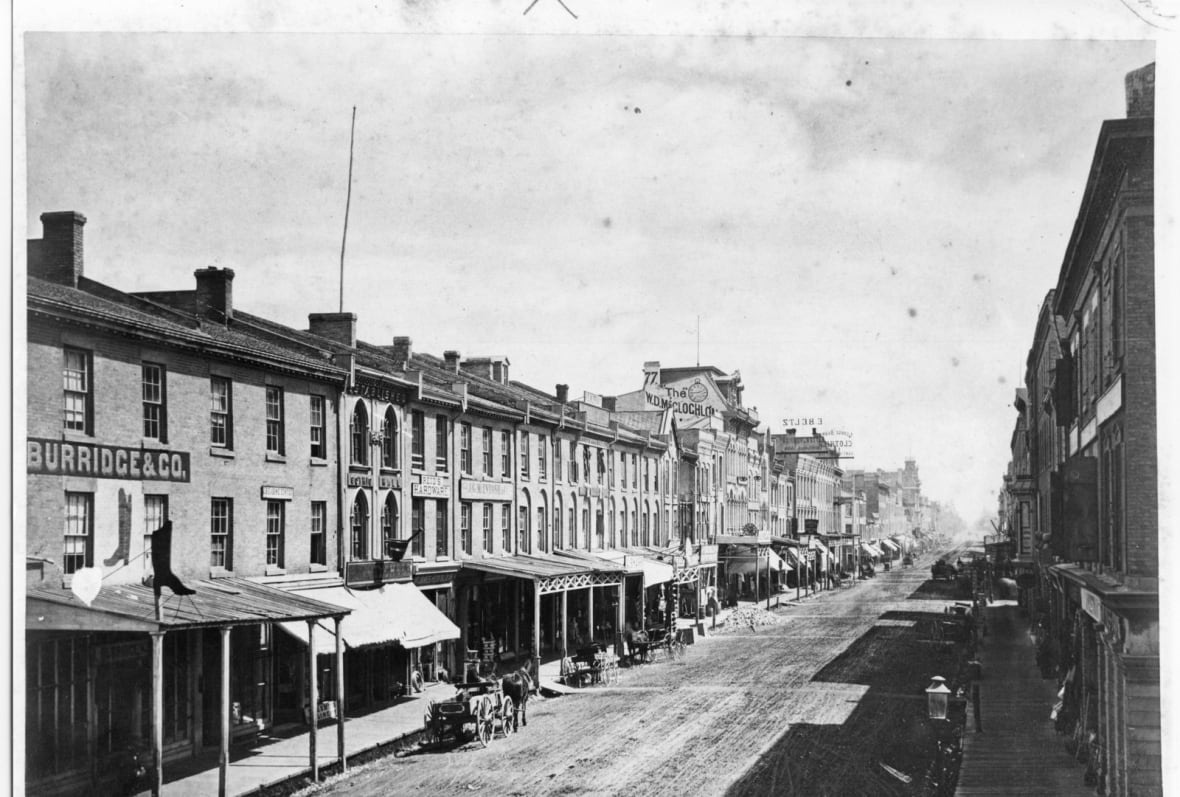

Their stories are now available to read online, and can even be visually traced on an interactive map from likely points of origin, to locations around London where they owned businesses and properties, and where meaningful events in their lives took place. The research group presented these findings last week at a celebration of Emancipation Day at Fanshawe Pioneer Village.

Records for people of colour not preserved.

Currently, three histories are presented in the online database: Mrs. Brown, Margaret Henderson, and simply "An Old Woman." Attempting to piece these stories together, and those of the other 13 freedom seekers, has been challenging, according to Alyssa MacLean, an assistant professor at Western and one of the project's co-founders.

"The reality is that a lot of records for people of colour were not preserved and a lot of records, especially for women of colour, were not really recorded in the system," she explained. "It was male-dominated and focused on the white population of London."

There was also the fact that many formerly enslaved people did not want to be found, MacLean said, explaining that many were scared of their former enslavers, or had families who had not escaped. In the case of An Old Woman, her account to Drew explicitly states her request for anonymity. In many cases, MacLean said, this wariness extended to census takers, police and other officials, and many preferred to just "go underground."

"I'm left to wonder about the totality of the experience that she's had," Gillis said of An Old Woman. "How she was able to adjust and who she interacted with… I just found myself wanting to know more about her life."

For Gillis, it was the women's stories that stuck with her the most. They wrote in more detail about their family members, and the impact of leaving their life behind and adjusting to new surroundings, she explained.

"I found those stories especially empowering because of that loss," Gillis said. "That's not to say that the men didn't experience similar loss, but theirs were told with a lot more emotion in regards to the familial life."

Even though the current goal is to trace the lives of these 16 individuals, the project's other co-founder, Miranda Green-Barteet, regularly tells the rest of the team that it's a "forever project." Both MacLean and Gillis agree.

"There's so much history that is left untold, so this project really and truly could go on forever," GIllis said.

"I continue to learn that these histories are not exactly well kept by the institutions, but they are really well kept by the communities," she added.

"So it really all comes full-circle, back to the Black individuals, Black families and what they're really willing to share with the rest of the community about their history."