Heart attack patient waits 13 hours in Moncton Hospital ER

'You always hear stories, then it actually happens to you,' man says of ordeal

Jonah Imeson says he'd heard plenty of stories about people waiting for hours in New Brunswick's emergency rooms and even dying before being seen by a physician, but then he had his own scare and he's still shaken.

The 35-year-old graphic designer, with Type 2 diabetes, said he waited 13 hours at the Moncton Hospital ER with chest discomfort, arm pain, nausea, high blood pressure and a sensation like heartburn before he was seen by a doctor, who told him he'd likely had a heart attack and could have died.

Imeson's story puts a face to the untold number of patients in New Brunswick who wait far too long in a hospital system that has openly declared a critical state of over-capacity.

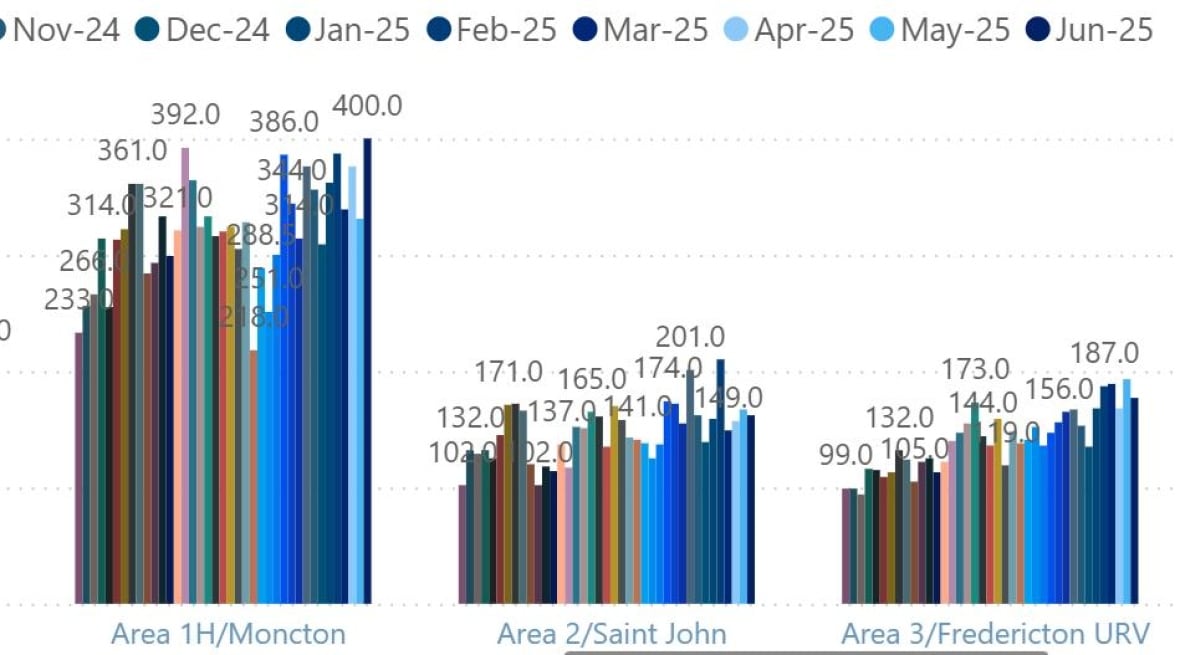

And although the Moncton Hospital has been left out of a new protocol demanding some hospital patients be fast-tracked into nursing homes — to help free up beds, including those in ERs — Horizon's dashboard paints a troubling picture.

It shows wait times in the Moncton Hospital ER, from triage to assessment by a physician, reached 400 minutes (6.6 hours) in June — the highest since April 2022 and well above the national target of 30.

That makes Imeson a remarkable outlier in a system already under-performing by a significant margin.

From 3 p.m. on June 4 until 4 a.m. the next day, he waited in a room so full, he lost his seat a few times after getting up to vomit and when he went to call his mother.

"You always hear stories, then it actually happens to you," he said of his ER experience.

Time-stamped text messages tell wait-time story

Imeson was able to reconstruct it from the text messages he sent home to his wife and to his parents in Oromocto. He didn't ask them to come to the hospital, he said, because he was concerned about his wife, who had to work the next day, and didn't want to trouble his mother or father.

The experience began at 1 p.m., when he was scheduled to see his dietitian on the hospital campus. He reported chest discomfort and a numb sensation in his arm.

The dietitian took his blood pressure, and when she got a reading of 210/119, she walked him to the ER herself.

At the triage station, Imeson reported that his own father had had a heart attack at 49 and that diabetes ran in the family.

Imeson was registered shortly after 3 p.m., then sat down to wait.

"While I was there, I started sweating profusely," he said. "I had to go to the bathroom a few times and vomit."

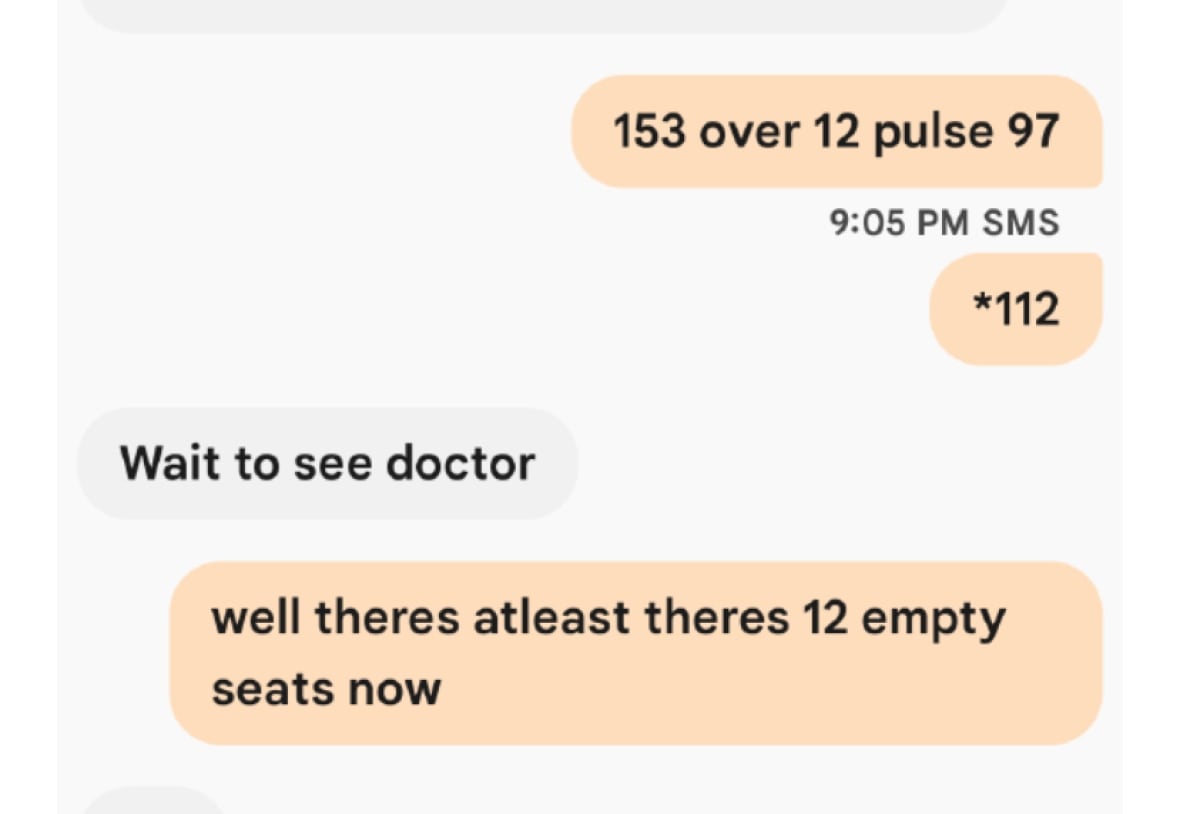

As the hours ticked by, Imeson updated his mother by text:

4:11 p.m. "168 over 107 pulse is 95."

5:13 p.m. "151 over 92. They gave me some Tylenol"

6:44 p.m. "147 over 78 pulse is 76 I just had to run and throw up again."

7:48 p.m. "148/78 pulse is 76. This heartburn feeling is weird."

9:05 p.m. "153 over 12 pulse 97 *112"

11:11 p.m. "160 over 94 pulse 90. room's filled"

As midnight approached, Imeson thought about leaving the hospital, walking down the street and calling an ambulance.

"To see if that might rush me in more," he said. "I guess a part of me never would have done that, but it definitely crossed my mind."

His mother texted him encouragement, told him to stay and that a doctor would likely see him soon.

Shortly after 4 a.m., Imeson saw a physician and was given an electrocardiogram.

It was the first time he heard from a doctor that he might have had a heart attack. More tests ensued.

"They did the ultrasound and they had mentioned that it appears the bottom section of my heart was damaged."

On June 6, Imeson was sent by ambulance to the heart centre at the Saint John Regional Hospital, where he underwent more examinations.

"When I went to Saint John and they did the ink dye test, it became more apparent what the situation was with that blocked artery. So that's why … it appeared damaged, because that artery was blocked."

Later that day, an ambulance returned Imeson to the Moncton Hospital, and he was discharged June 8.

On Monday, June 16, he returned to work, while taking medication.

Once he had his "foot in the door" and could speak to doctors, he said, his care was excellent.

Cardiologists say heart attacks need immediate attention

CBC News contacted Dr. Zeeshan Ahmed, a cardiologist at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa, for a better understanding of what happens when a heart attack occurs.

He was not asked to diagnose Imeson or comment on his care.

Ahmed said heart attacks are caused by the gradual buildup of plaque in the artery and the sudden rupture of that plaque, which then blocks the artery.

"And when that specific artery becomes blocked, the portion of the heart muscle it's supplying will have a lack of blood supply, and as a consequence those muscles will start to die," he said.

Ideally, patients presenting with heart attack symptoms would receive an electrocardiogram test within 15 minutes of arrival at the hospital.

"Someone presents with chest pain, immediately, an ECG within 10 to 15 minutes, and then the physician has to read it," Ahmed said.

An ECG is a simple test, where a lead is attached to the patient's chest and the doctor looks at the electricity the heart generates, which helps a diagnosis.

Ahmed said chest pain happens when the artery is partially blocked or blocked completely, and it's important for patients who do feel severe chest pain to get medical attention as soon as possible.

"The longer they wait, the heart muscle that is not being supplied by blood will eventually die," he said. "And as it dies, it will start to scar."

"I urge people to come to the hospital. Don't sit on the symptoms. Don't delay, especially if there are risk factors like a family history of heart disease, high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, or a history of smoking."

Ahmed said symptoms include a sensation of chest tightness or discomfort, a feeling the pain or tightness is travelling down one arm or both arms or up to the jaw. Patients may also have sudden sweating or shortness of breath. They might feel lightheaded or nauseous. They might also feel pain in their upper stomach.

Horizon Health said it could not comment on Imeson's file for privacy reasons, but provided a written statement from Bonnie Matchett, the network's clinical director of emergency and critical care.

"We can confirm a high volume of patients were experiencing high acuity medical needs in Horizon's The Moncton Hospital (TMH) Emergency Department (ED) on this date," Matchett wrote.

She said Horizon wants a "positive patient experience," and people concerned about the care they've received should communicate with a Horizon patient representative.

Imeson said he's not sure he'll go to the patient advocate. He's focused on recovery.

He is also reflecting on what he might have done to get seen more quickly — or whether causing any fuss would have been proper.

"I just assumed they were doing the best with what they had and I just stuck through to the end," he said.

"But I was concerned if I made a scene, would they ask me to leave? And would it even have been fair for me to do that to them they were as busy as they were."