Getting few answers in brother's workplace death, woman's persistence prompts fresh look at case

Andrew Gnazdowsky died Oct. 16, 2020 while doing surveying work at N.S. Power reservoir

When Nicole Gnazdowsky can't sleep, she often finds her mind turning to the sunny October day her younger brother, Andrew, drowned at work.

The civil engineer from New Brunswick had been trying to swim out to retrieve a piece of surveying equipment about 100 metres from the shoreline of a Nova Scotia reservoir when he ran into some kind of trouble.

As a team of divers recovered the 26-year-old's body last fall, his sister dipped her toes in the water at the Marshall Falls beach, not far from the dam that is part of Nova Scotia Power's Sheet Harbour hydroelectric system. Off in the distance, she could see homes with docks jutting into the water.

"It doesn't look like a dangerous spot at all. And my brother was a competitive swimmer. He was healthy. He was six feet tall, like a big guy. He could have swam that at any point in time. And so while you're standing there, it's like, how did that happen here, of all places?" Gnazdowsky told CBC News.

"To me, it's always been what's the story behind the drowning? Did he get hit with the piece of equipment? Or was it because the dam was on?"

Concerned about the scope and quality of the Labour Department's investigation, Gnazdowsky has spent the last two months asking provincial officials for accountability and doing her own research into her brother's death — one of 18 fatalities stemming from traumatic injuries at work last year in Nova Scotia.

Her tenacity has prompted provincial officials to review and revise the autopsy report, assign a new lead investigator to the case, and acknowledge the Gnazdowsky family has been let down by a system put in place to provide answers and bring closure.

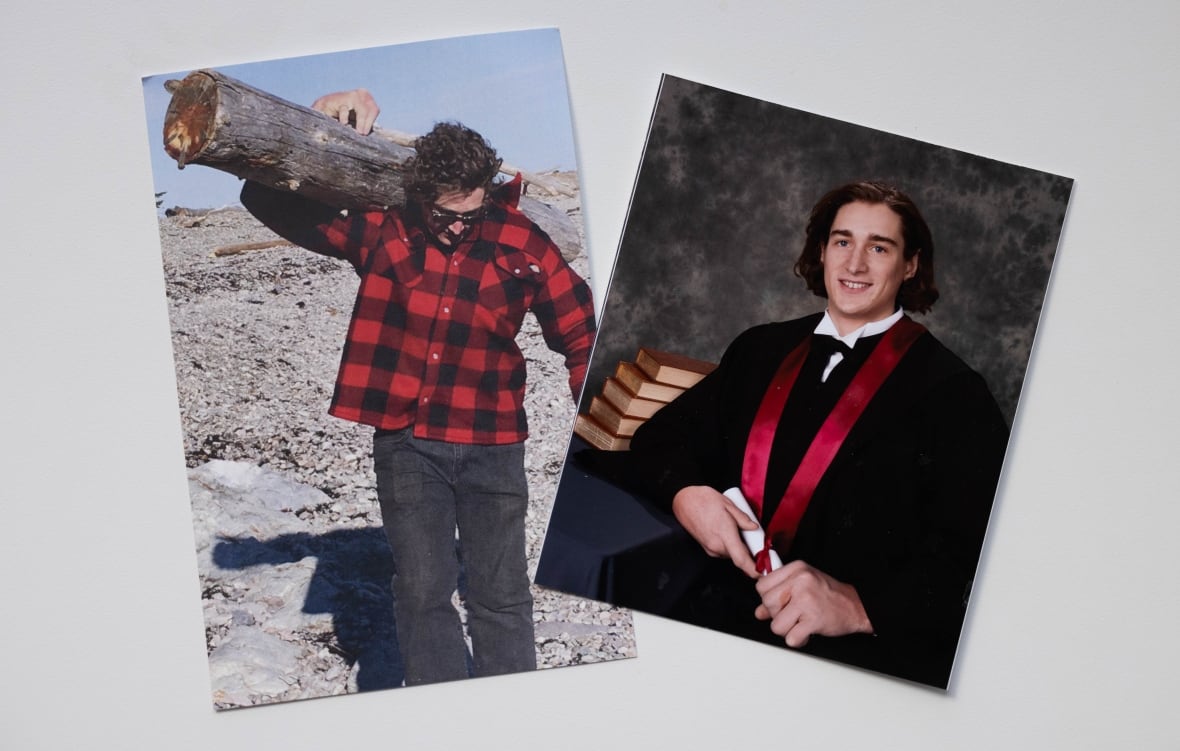

Andrew Gnazdowsky cherished his family and his large circle of friends sprinkled across the country. He cheered loudly for his beloved Saskatchewan Roughriders, showered affection on his two dogs, Mollie and Ellie, and had recently settled into his first home with his girlfriend in Rothesay, N.B.

"You could feel it when you walked in the room, he was just the happiest guy, the nicest guy…. The most loyal human being I've ever met," said Nicole Gnazdowsky, who considered her brother her best friend.

"He was really ... at the prime of his life, just starting to get it all together and make those moves forward."

'All somebody had to say was no'

On Oct. 16, 2020, Andrew was helping a colleague conduct a bathymetric survey — a type of underwater mapping — using a piece of equipment that was controlled remotely, similar to a drone, and floated on the surface of the water. The pair worked for Brunswick Engineering and had travelled from Saint John to collect data at the dam.

But that Friday afternoon, the equipment stopped responding and began to drift, according to his autopsy.

His sister said it was no surprise to learn that Andrew volunteered to get it, stripping down to his boxers and entering the water.

"He was on site that day because somebody else had left the company and he's the kind of guy that will step up to help out when there was a need for it," said Gnazdowsky.

"It could have been so simple. All somebody had to say was, 'No, don't do that.'"

3 companies involved

Officials from Nova Scotia's Labour Department have confirmed to Gnazdowsky there were at least three other people nearby when Andrew went into distress: his colleague who attempted to swim to him, a Nova Scotia Power project manager, and a representative from Gemtec, the geotechnical engineering contractor that hired Brunswick Engineering.

Photos Gnazdowsky found from her brother's phone showed he and his coworkers previously used a kayak and another type of small boat to conduct surveys on the water.

While he had access to a boat during another site visit on Nova Scotia's south shore on Oct. 15, she said no one has been able to explain to her why he didn't have a boat when he went to retrieve the equipment on the day he drowned.

All three companies declined to comment or answer questions from CBC News about who was responsible for providing safety equipment and a boat, citing the ongoing investigation.

"There's nothing more important to us than the safety of our employees, contractors and customers. We continue to co-operate with the investigation," Nova Scotia Power said in a statement.

The utility's 2018 Contractor Safety Program, which sets out standards for contractors and the employees who manage them, categorizes working on the water or with watercraft as a high-risk activity that requires a safety plan, a risk assessment and PPE.

The program shows an example of a job hazard analysis checklist that says any work around the water involves communicating water flow information and boating safety precautions, with tasks assigned to either the contractor or a representative from the utility.

Investigations 'can be time-consuming'

The Labour Department declined to be interviewed by CBC News.

"The [occupational health and safety] division has had regular communication with the family to provide updates on the ongoing investigation as best we can," said Krista Higdon, a spokesperson for the department, in an emailed statement.

"Workplace fatality investigations are complex and need to be carried out in a detailed and thorough manner which can be time-consuming."

Questions about facial bruising

The Gnazdowsky family didn't have any contact with the Labour Department until about a month after Andrew's death. They had reached out to WorkSafeNB, the workers' compensation board in New Brunswick, to try to find out what was happening and it eventually connected them with the investigator assigned to the case.

Gnazdowsky said one of their first questions related to the cause of bruising on Andrew's face. It was so pronounced that the funeral home warned the family before their viewing, she said, so she was puzzled when the Labour Department investigator wouldn't tell them if it was part of the investigation.

"Why can't you say yes or no? Because we know it, we saw it, it haunts my dreams. Are you going to look at it?" she said.

The family heard little from the investigator for months and when she referenced being busy with another incident in an email in late February, Gnazdowsky got worried and started trying to get answers herself, eventually requesting her brother's autopsy.

Autopsy report amended

The report showed Andrew's cause of death was drowning and the medical examiner's office did not note any medical issues that could have caused him to go into distress. His older sister was surprised to see only a brief mention of a "faint abrasion" on his lip and nose, which didn't line up with the dark bruising she remembered, so she sought to find out why.

After discussions with multiple people from the medical examiner's office who reviewed photos taken during the autopsy, the office issued an amended report noting some discolouration on part of Andrew's face in addition to the abrasion around his nose, which "may represent orbital contusion."

The report said the facial injuries "were not independently life-threatening," and it could not be determined with any degree of confidence whether they happened after death or when Andrew was trying to recover the equipment.

Dr. Matthew Bowes, Nova Scotia's chief medical examiner, reviewed the case in mid-April as a result of Gnazdowsky's inquiries and explained that bruising can become more pronounced on a body as days progress.

Bowes also told her he would personally call and alert the Labour Department of the changes.

Another error Gnazdowsky flagged, which was subsequently corrected, was the date of Andrew's drowning in the original autopsy report. It indicated the incident happened a day later, on Oct. 17 — information the medical examiner's office said came from the RCMP.

Gnazdowsky wondered if that was significant since she was told the dam had been on when her brother went in the water, but was turned off when divers started searching for him.

By that point, she had started reading about other workplace fatalities, including the 2015 death of Luke Seabrook, a commercial diver who was killed after getting stuck underwater while inspecting a gate that measures the flow of tides at Nova Scotia Power's Annapolis Valley tidal station. Gnazdowsky wondered if a current or pressure related to the dam factored into her brother's struggle at all.

Potential conflict of interest

As part of her digging, Gnazdowsky looked up lead investigator Courtney Donovan's profile on LinkedIn — a professional networking site — and questioned whether it was a possible conflict of interest that Donovan previously worked for Nova Scotia Power's parent company, Emera.

On March 3, Fred Jeffers, executive director of occupational health and safety with the Labour Department, told Gnazdowsky he was reaching out to the Public Service Commission to determine whether there was a conflict.

Officials later informed the family they had assigned another lead investigator. The Labour Department did not respond to questions from CBC News about why this change was made or whether the commission had made a ruling.

Lack of information familiar

In early March, Gnazdowsky met with Premier Iain Rankin, her MLA, who subsequently helped arrange a meeting with Duff Montgomerie, deputy minister of the Labour Department, and Christine Penney, the senior executive director.

Gnazdowsky asked Shannon Kempton, who is all too familiar with workplace investigations, to join her for the meeting.

Kempton's father, Peter, was an auto mechanic who suffered fatal burns while attempting to remove the gas tank of a derelict minivan at an auto shop in Dartmouth, N.S., in September 2013. After a long court process, his employer was fined $27,000 last year for workplace safety violations.

Kempton said eight years ago, she was in the same position as Gnazdowsky — asking questions and not getting answers.

"You're made promise after promise from the department, they never follow through," she said.

"For families who are going through the worst time of their life, not to have any idea what is happening, it's so frustrating for me to see happen over and over and over again."

'Why are they trying to hide this?'

Last year marked the deadliest year in a decade for acute workplace deaths in Nova Scotia. At the end of April, the Labour Department still had open investigations into 14 of 18 fatalities.

CBC News obtained some details about the dates, locations and industries involved through freedom of information laws, but many descriptions of the incidents remained redacted. Unlike some provinces, Nova Scotia doesn't automatically release information about fatalities.

Kempton wants the lack of public transparency to change, too.

"Why are they trying to hide this?" she said. "Is it because the department … isn't doing their job in enforcement and inspection prior to an accident, and they don't want people to realize how bad things really are?"

Charges under the province's Occupational Health and Safety Act can be laid up to two years after an incident.

But Gnazdowsky worried if her family waited that long to see what would happen in Andrew's case, they still wouldn't be privy to information gathered as they were advised they'd also have to go through freedom of information.

Failure to meet the minimum standard

In a phone conversation last week that Gnazdowsky recorded and shared with CBC News, Scott Burbridge, manager of investigations with the Labour Department's safety branch — to whom the lead investigators on fatality files report — told her the department's practices regarding communication and information shared with families could be improved.

"We failed to meet even the minimum, the existing minimum standard with you and your family in this," he said.

In response, Gnazdowsky said she was concerned what might have happened had she not stepped in.

"There is no question in my mind whatsoever that you accelerated the pace of this," Burbridge replied. He confirmed to CBC News he considered both statements factual.

Speaking later in an interview, Gnazdowsky said the whole experience has made her question the rigour to which the province is looking into deaths of workers on the job.

"While you're planning the funerals, and you're selling their houses, and you're going through their belongings, and trying to pick grave plots and headstones and all of this horrible stuff that we now have to face as a family, at a bare minimum you want to trust that the department and the people who are in charge over there are doing their jobs, and they're not," she said.

MORE TOP STORIES