Connecting to culture, leaning on kinship key to how these Indigenous fathers are breaking traumatic cycles

'It's to learn that, yes, we do need support, we do need help, and it's OK to be vulnerable'

This piece was originally published on June 13, 2019.

It's 34 C in Saskatchewan's Qu'Appelle Valley the day Philip Brass leads his son Forrest to one of their favourite spots to hike.

Brass is wearing a custom pair of beaded moccasins. They help him walk with ease through bushes and over the rough prairie terrain. His seven-year-old son wears his hair in two thick, neat braids that flow down to his waist.

Forrest lost his hat that morning, so his head is drowning in one of his dad's old baseball caps to help protect him from the sun.

The young boy carries a bow and arrow, stopping every once in a while to shoot, only to run ahead and retrieve the arrow from the tall grass.

Brass, who hails from the Peepeekisis First Nation, is a land-based educator with a few schools and other organizations in the Treaty Four region, so taking his son out on the land is second nature to him.

It is a tradition he is passing down from his late father, Oliver Brass.

Philip lost his father 22 years ago — and the subject of fatherhood still makes him tear up. He recalls a father who "introduced me to a lot of wonderful things in the world." He imparted skills upon him and travelled with him, but "there was a great sadness that he carried."

"He was a very loving man," said Philip. "He was an incredible father but, of course, as all Indigenous men of his generation, there was a lot of trauma in their lives."

Oliver was an accomplished academic, doctor and university professor. A minister, he eventually left Christianity behind and embraced his Indigenous culture, learning the Saulteaux language and becoming a sundancer and ceremonial man.

"In the mid- to late-80s he was going through a radical decolonization process and, being the academic that he was and the very spiritual man that he was, I don't think he had any peers to really to bounce that off of, so he felt very lonely and I think that that's what eventually took him," said Philip.

He said their relationship become tense in his teens as his father's drinking became more of a problem. He, too, was introduced to drinking by his father. It was something they'd often do together. Philip "experienced shame and embarrassment as a teenager and as a young man" over his father's drinking, as he saw him "descend into a very unfortunate place."

He was 20 when his dad died.

"I see other families who were completely obliterated [by alcoholism]," said Philip. "I think in my community, the boys that I work with, it seems that at least probably 75 per cent don't have a father an active father in their life."

"It's a long legacy of broken families. ... It's tangled and I think residential schools are just one component of that unravelling."

Witnessing his father turn from a great man into a shell of what he once was, was part of Philip's inspiration to give up drinking 10 years ago. Now, he's working to build a different home life for his son, whose middle name is Oliver, and the five teenage boys he mentors and has informally adopted over the years.

"You don't really blossom into who you are as a man unless you are sober, you know? Spiritually you're stunted; intellectually you'll be stunted," said Philip.

Instead, Philip has brought Forrest to ceremonies — and even sweats — since he was a baby.

"That land-based relationship I think is very vital, especially as young Indigenous people and as a young Indigenous man. I think it's really crucial to a healthy identity and try to maintain those connections."

Accepting vulnerability

Robert Innes said learning how to be vulnerable and exploring past hurts can help Indigenous men heal — not only for themselves, but their families and communities as well.

"Acknowledge our shame of what we have done to others and what has been done to us, coming to grips with those realities, I think, allows men to become vulnerable — vulnerable in a way that they're told that they shouldn't be," said the associate professor of Indigenous studies at the University of Saskatchewan, who co-edited the book Indigenous Men and Masculinities: Legacies, Identities, Regeneration.

"So, it's to learn that, yes, 'We do need support. We do need help,' and it's OK to be vulnerable and those are tough, because that's not what we learned. To be an Indian man today is not to be all those things."

He said a macho culture has driven many Indigenous men to negative lifestyles.

"One of the things that's difficult to learn — to relearn or to unlearn — is the idea that Indigenous men are not deviant, are not born bad, you know? Or dangerous people ... and so it's unlearning the fact all the negative, racist stereotypes that have been imposed on us," said Innes.

"Allowing yourself the ability to think that, 'Yes, I am good and I can be good,' because we have been told for many years we are actually bad."

2 brothers ripped apart

Growing up on the White Bear First Nation in Saskatchewan, Dez Standingready said he did not have anyone around to teach him, "how to be a man."

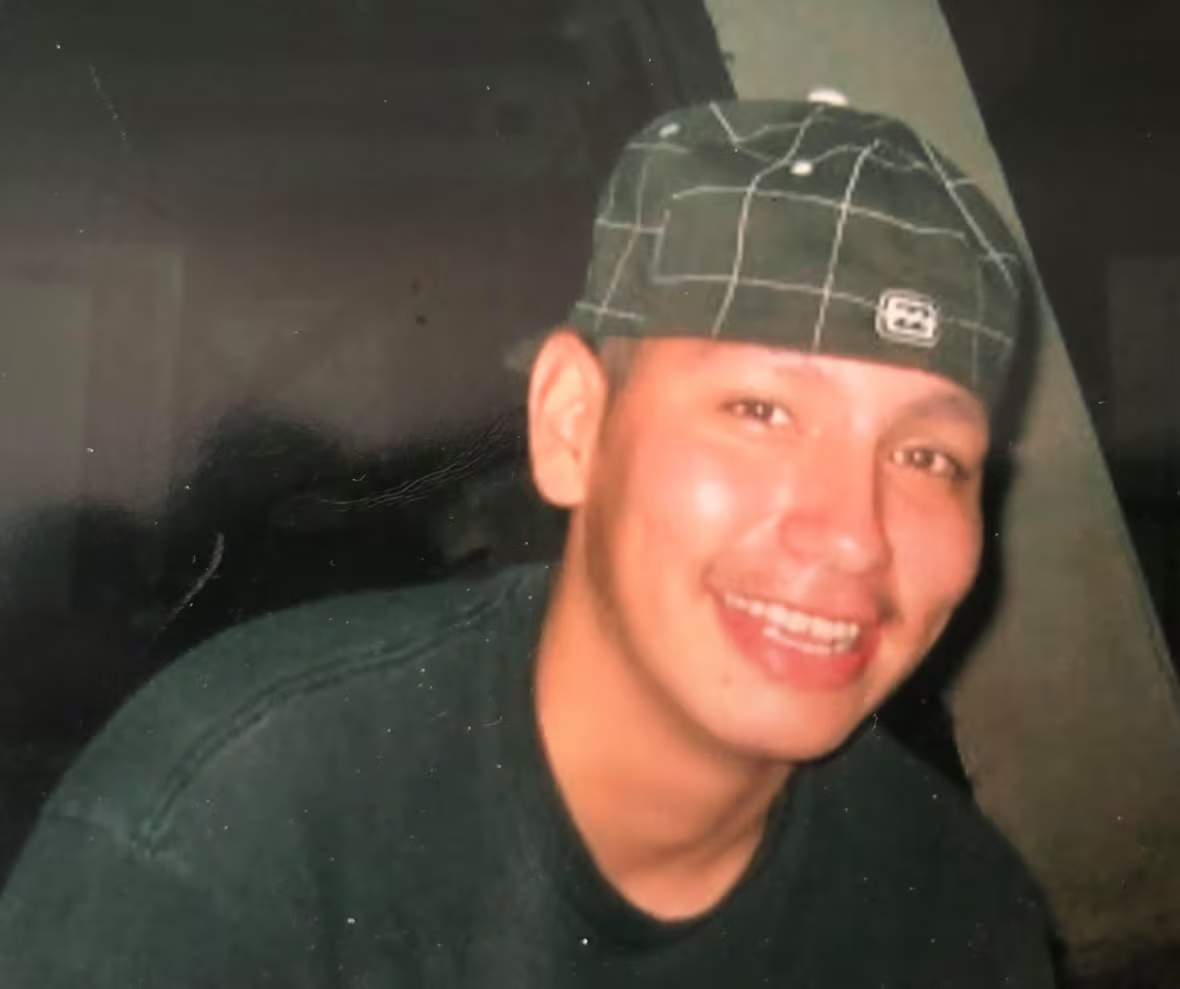

Standingready's mother had him when she was 16. At the age of 37, he has yet to meet his father. He said he didn't have many positive male role models to look up to either. But what kept him going was knowing he and his younger brother, Chase McKay-Standingready, would always have each other to rely on.

That was until the boys were sent to two different Indian Residential Schools. Standingready was 13 years old and his brother only eight at the time.

"I still remember that day when I got dropped off in Lebret [Sask.], my brother was sitting in the back seat and he was looking out the back window and he was crying for me. I'm just like waving at them, and I didn't know what I was getting into - what I was in for at the time," said Standingready.

Nine years later, in 2008, his brother was fatally shot by an RCMP officer. He was 21 years old. His death was deemed a form of suicide.

McKay-Standingready had just become a father. His daughter was one year old at the time of his death.

"I just look at her sometimes and I can just see his eyes and it just makes me cry," said Standingready.

Standingready is now a single father to two boys aged 15 and eight. He also shares custody of his four-year-old daughter. He said he had a difficult start to fatherhood in the beginning. In order to pay the bills in his early 20s, he turned to drug dealing.

It was not until he faced some lengthy jail time that he turned his life around. He enrolled in the business administration program at the Saskatchewan Indian Institute of Technologies but struggled financially raising his eldest son, Ashton, alone in a city where he had no family to lean on. Standingready often took Ashton with him to his classes because he could not afford daycare.

"Personally I felt like I was a burden to the other students, to the school, but after a while and I saw the love that the fellow students and the teachers had. They kind of got attached to my son as well."

Standingready said this experience shaped his view on the importance of kinship in parenting.

"I think that kinship is a big factor in our way of life, right? We always help each other out no matter what — whether you're related or not, we always pass those kinship patterns of helping, loving, and trying to help each other out," Standingready said.

He encourages people to offer help to parents, even if they don't ask for it.

"I wish I had somebody to say, 'Hey, bro, do you need help?' You know? That's all that I needed at the time."

He said that is the kind of relationship he had with his late brother, and it is something he hopes to instill in his sons, who are the same age apart as he and brother were.

"I need for them to be able to just live and love each other every day and look after one another."

The valley dips in the background as Forrest grabs his hand drum and begins keeping a steady beat. Philip joins in with a ceremonial song that can only be passed down like this: in person, in prayer.

Forrest stares up at his father and tries to keep up as he sings these sacred songs, songs that must be earned.

"It's such a gift to be a father," said Philip. "It keeps me youthful and be the best person I can be. We need to all be thinking deeply and acting courageously in how we raise our children."