If there's a tug-of-war over conservatism, only one side is really pulling

Two former Conservative leadership candidates make bids for power and influence

Last week, two former candidates for the leadership of the Conservative Party announced new bids for power and influence.

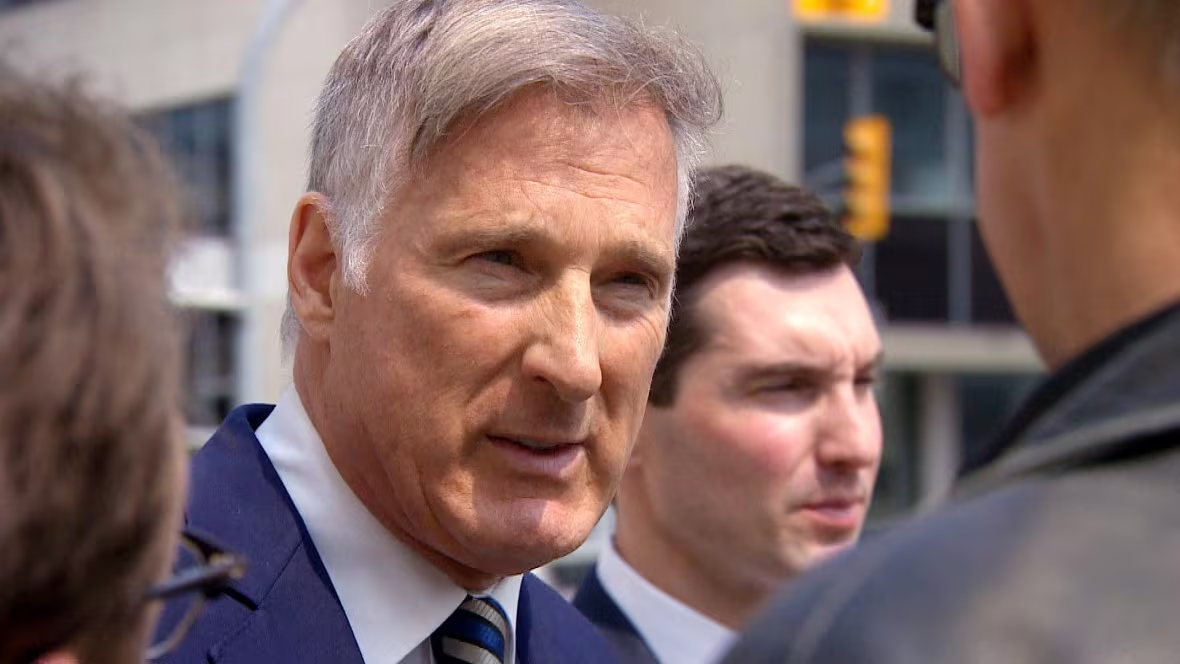

Rick Peterson, who finished 12th in the Conservative leadership race of 2017, announced that the Centre Ice Canadians, an organization he launched last year, is looking to establish a new "centrist" political party. And Maxime Bernier, who finished second in 2017, announced he would be running in a byelection in the Manitoba riding of Portage-Lisgar under the banner of his own People's Party.

In theory, this might mean Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre will soon face duelling challenges from both the right and the middle. In reality, the reactionary forces that Bernier represents seem more powerful than Peterson's project might ever be.

If this is a tug-of-war, only one side is really pulling.

In Bernier's telling, the Conservative Party is unwilling or unable to fight the necessary "cultural battles." Stephen Harper's former foreign minister once sold himself as a principled libertarian whose calling card was a promise to abolish supply management. He has since found other interests.

Turning up in Manitoba last Thursday, he vowed to fight the "woke cult" that is apparently "demolishing the traditional pillars of our society and aims to establish a twisted and profoundly sick vision of the future." In his remarks to supporters, his grievances included "cultural marxists," "transgenderism," "drag queen story hour in our schools and libraries" and "moral and cultural degeneracy," as well as "mass immigration," "climate hysteria" and the "cult of diversity."

Such stuff might create room for Poilievre to present himself as a reasonable conservative in contrast to Bernier's divisive extremism. But that might be difficult as long as Poilievre also seems inclined to chase the anti-woke vote.

The anti-woke primary

A day before Bernier's campaign announcement, Poilievre decided to attack a decision by teachers at a Quebec elementary school to replace their traditional marking of Mother's Day with a celebration of all parents — a decision reportedly made out of consideration for students who don't have a mother or father or who are currently in foster care.

"The woke wants to delete Mother's Day," Poilievre tweeted. "This ugly and weird ideology — which [Justin] Trudeau endorsed at his party convention — wants to delete everything except the state which would control everything and everyone."

Maybe Poilievre would be tweeting about the sinister forces apparently trying to deny mothers their special day even if Bernier and the People's Party didn't exist. But the Conservatives don't seem unbothered by Bernier's arrival in Portage-Lisgar.

"Maxime Bernier has always been an opportunist. He will go anywhere, say anything and take any position just to bask in a spotlight," Conservative House leader Andrew Scheer tweeted on the day Bernier declared his candidacy. "I know from experience: he is always more focused on his own self-promotion than on any of the issues he claims to care about."

Scheer then went to Manitoba to make that case against Bernier in person.

It's hard to imagine Bernier actually winning that byelection in Manitoba. Even if the PPC candidate finished second in Portage-Lisgar in 2021, the Conservatives still won the riding by more than 30 points.

But Bernier doesn't need to win to be successful. He just needs to show that he can still draw significant support and pull votes away from the Conservative Party.

The centrists belatedly get in the game

Bernier is at least on the ballot — which is more than can be said for anyone associated with the Centre Ice Canadians, the organization originally launched as Centre Ice Conservatives.

The group drew a former premier, a former provincial cabinet minister and a former Conservative MP to their first conference last summer, a month before Poilievre was elected leader of the Conservative Party. At the time, it seemed there might be a real opening for a moderate conservative party — perhaps something like the former Progressive Conservative party that existed from 1942 to 2003.

But Peterson explicitly dismissed the notion of starting a new party. "Nobody" wanted to do that, he said, comparing the task of setting up 338 riding associations across the country to getting 338 root canals.

Less than a year later, the thought of a few hundred root canals has apparently gained some appeal. But the broader interest in the Centre Ice project remains uncertain.

Shortly before he was deposed as Conservative leader in 2022, Erin O'Toole told his caucus they had to choose between two paths — between being "angry, negative and extreme" and choosing "inclusion, optimism, ideas and hope." But if anyone in the Conservative fold is unhappy with the path the party ended up choosing, they've been very quiet about it over the past year.

Until moderate conservatives seem like a constituency Poilievre needs to worry about, he's likely to spend more time worrying about his far-right flank.

It's possible to overstate the impact of the People's Party on the 2021 election. While the PPC drew nearly five per cent of the vote, it didn't have a decisive impact on the national result. But some PPC voters were people who previously voted for the Conservative Party — and it's plausible that vote-splitting cost the Conservatives somewhere between three and seven seats.

It's also possible now to see the PPC as a significant piece of a three-part path to Conservatives winning at least the most seats in the next election. If Poilievre can maintain the Conservative vote from 2021 and win (or win back) some of the PPC vote, and if the Liberal vote slides even further than it already has, he could emerge from an election with a plausible shot at power.

Poilievre's leadership of the Conservative Party seems to align with such a path — he certainly hasn't pivoted to the centre since becoming leader last fall. And so, Portage-Lisgar might be viewed as a test of whether Poilievre has begun to win over some of the PPC vote.

Unless or until he faces a real challenge from moderate conservatives, Maxime Bernier and the PPC vote might be Poilievre's guiding concern.