Sudbury was a stand-in for the moon and other little-known (Canadian) things about the Apollo program

While Canadian astronauts may not have visited the moon yet, our achievements are part of Apollo history

This story is part of Moon Landing: 50th Anniversary, a series from CBC News examining how far we've come since the first humans landed on the moon.

In a few days, the world will mark the 50th anniversary of humans first setting foot on the moon.

Apollo 11 was an ambitious mission that would see three men — Neil Armstrong, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin and Michael Collins — head to the moon, with the ultimate goal of walking on its surface.

The almost-Herculean task on July 20, 1969 wasn't only made possible by the effort put forth by the three men, with Armstrong and Aldrin being the first men to set foot on another world. It was also thanks to more than 400,000 people who worked behind the scenes.

And you may be surprised to know that Canada played an important role in the ambitious project that took humans far from home. Here are a few facts about Canada's role in this historic mission.

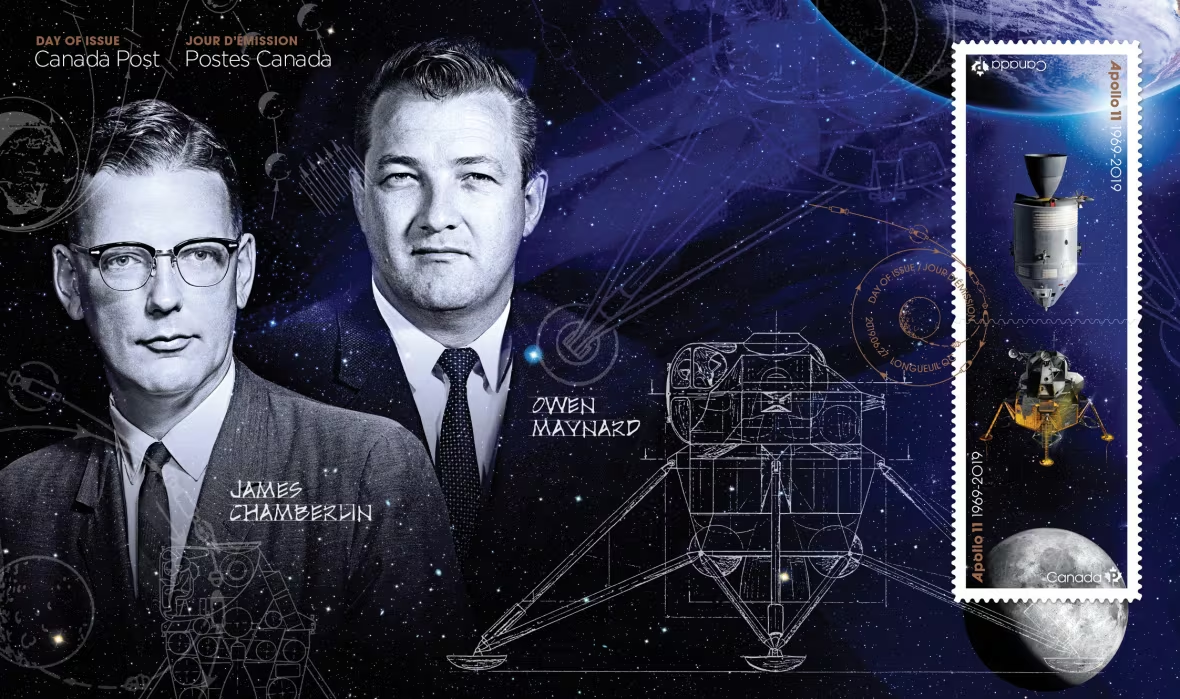

From Avro to Apollo

The Avro CF-105 Arrow — a supersonic jet designed and built in Ontario in the 1950s — was ahead of its time. Still, the federal government cancelled the program in 1959, leaving roughly 25,000 people unemployed. It has long remained a black mark in Canadian aviation history.

At the same time, however, NASA was searching for some of the world's top engineers for their space program.

Knowing the shuttering of the Avro Arrow program would leave many talented engineers looking for work, NASA officials flew to the Avro plant, located just outside of Toronto, three weeks after its demise and recruited 13 Canadians.

Among them was Owen Maynard, from Sarnia, Ont., who originally worked on the Mercury capsule that would carry U.S. astronauts into space for the first time. He was later moved to the Apollo program.

NASA was struggling with a big question at the time: What was the best way to get to the moon?

Some believed it was a direct trip in a single spacecraft.

But not James Chamberlin, a B.C.-born former top Avro engineer. He suggested a two-ship rendezvous in space, with a command module that would orbit the moon and a lander that would head to the moon's surface.

NASA ultimately chose Chamberlin's two-craft idea and, over the years, Maynard headed the design of the spacecraft.

Legs to stand on

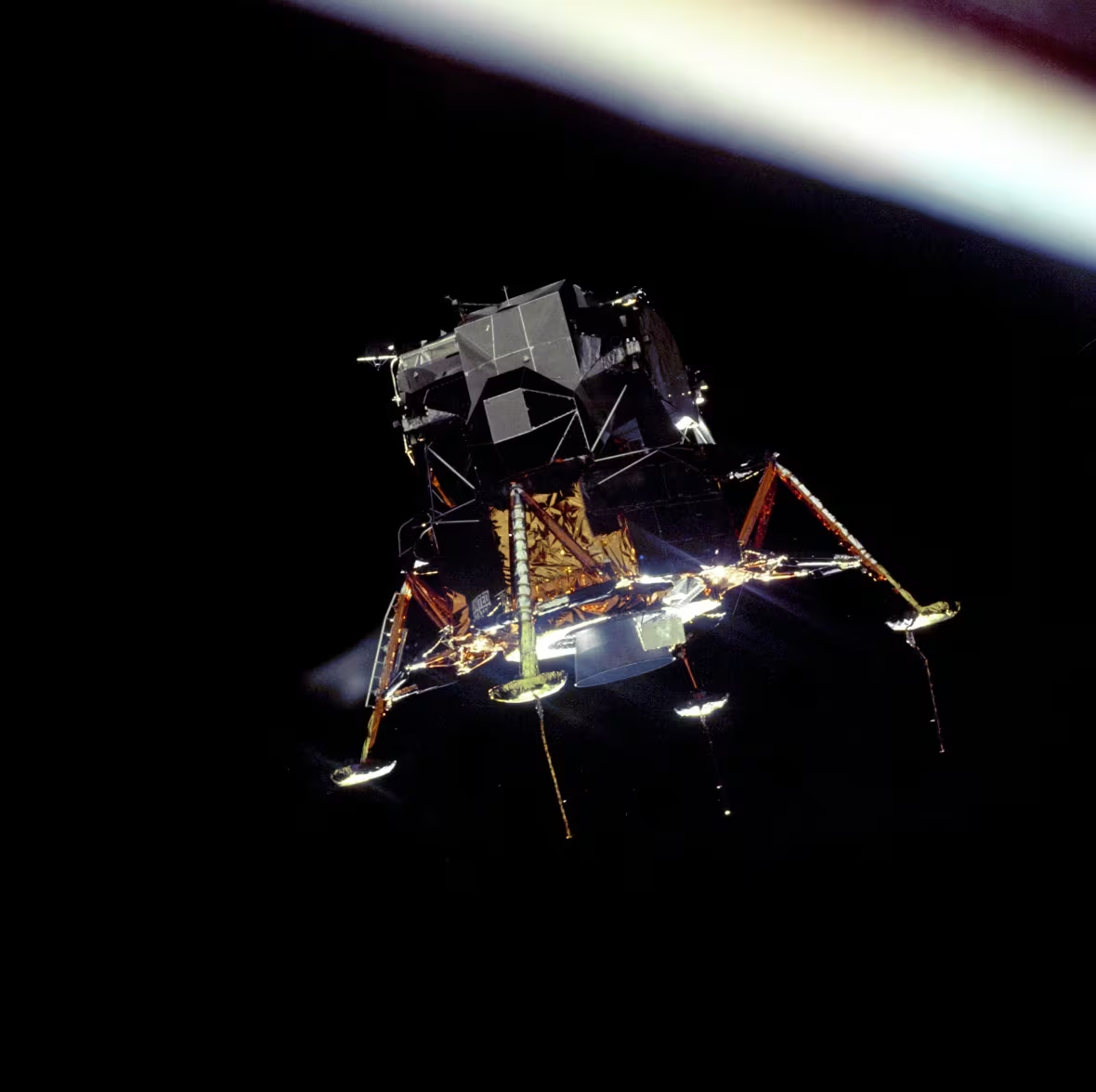

Not only were Canadians highly involved with designing the vehicle that would take humans the furthest they'd ever ventured, but they were also working on the physical components of the lander itself.

Based in Longueuil, Que., Héroux Machine Parts Limited (now Héroux-Devtek) was given the equivalent of what today would be a $2-million contract to build eight telescopic legs with shock absorbers for the Apollo lunar lander.

That might sound like a simple task, but at the time, no one knew what the lunar surface was like. Was it soft? Rocky? Cratered? There was also a real fear by the public that the lander could be in danger of sinking.

You may notice in that black-and-white video showing Armstrong exiting the lander that there was a bit of a drop from the bottom of the ladder to the landing peg. That's because the lander didn't sink, as engineers, designers and scientists thought it would, so the astronauts needed to hop down before setting out on the moon.

Dr. Apollo

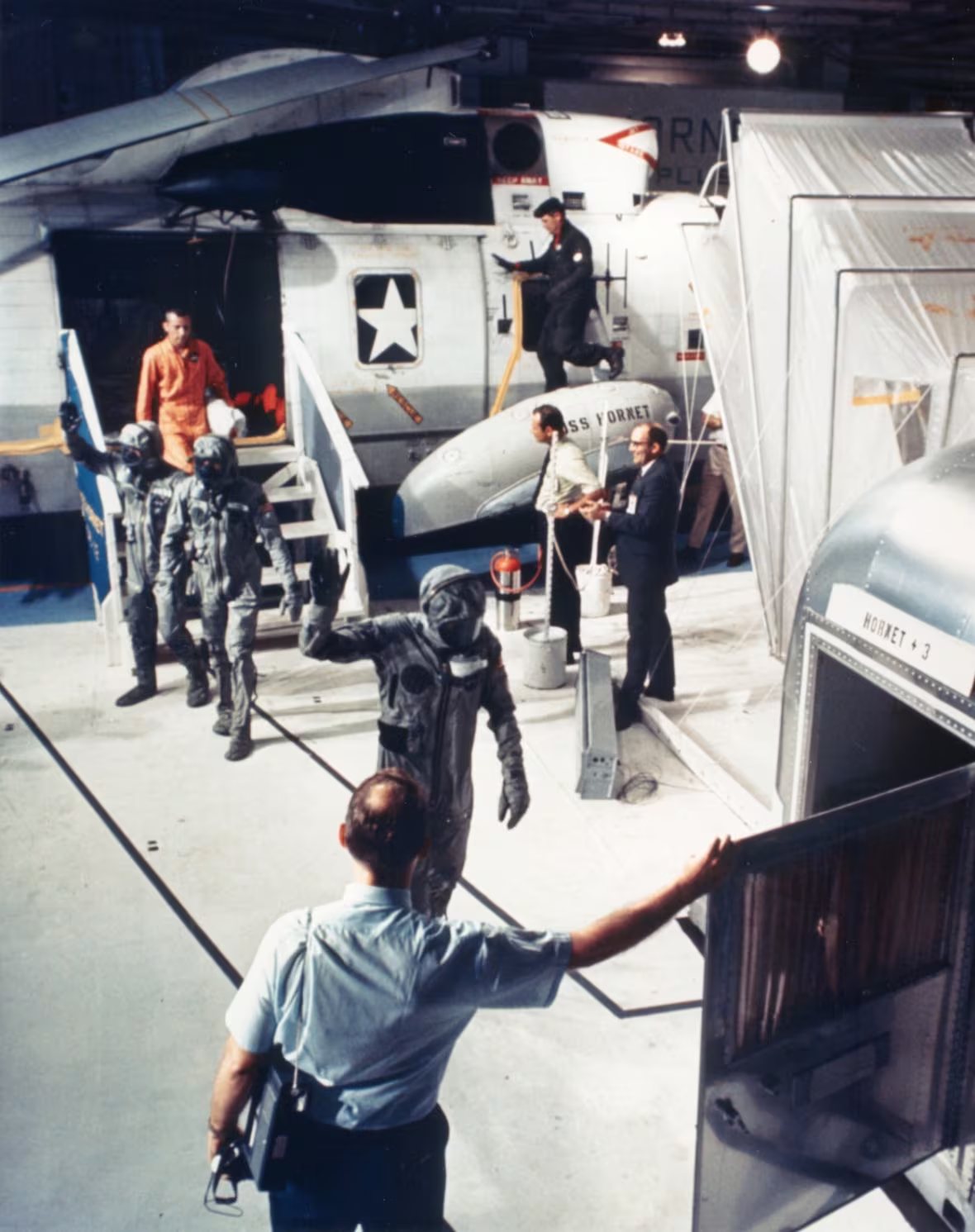

In addition to uncertainty about the makeup of its surface, doctors didn't know whether the moon contained any contaminants or germs. So when the three astronauts returned on July 24, 1969, they were promptly put into quarantine, due to a fear that they could have brought back some "moon germs."

Once the Apollo 11 astronauts splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, about 1,450 kilometres southwest of Hawaii, biological isolation suits were tossed to them through the opened hatch from a helicopter. Once the men reached their recovery ship, the USS Hornet, they were quickly transported into a Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), essentially a converted 10-metre Airstream trailer complete with air ventilation and filtration systems, beds, a living area and a kitchen.

But they weren't alone in their shiny temporary prison: Also quarantined was NASA recovery engineer John Hirasaki and NASA doctor William Carpentier, a graduate of the University of British Columbia.

Born in Edmonton, Carpentier moved in 1965 to the Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center), where he would complete a three-year residency in space medicine.

Not only was Carpentier a great physician, he was also a strong swimmer — a skill that put him ahead of other contenders for the job.

Hot stuff

While there are many challenges with getting to the moon, returning astronauts safely is also a big task. Any object returning to Earth has to travel through our thick atmosphere — and getting through it generates friction and thus heat.

Bryan Erb, from Calgary, was one of the men who helped work on developing the heat shield that would protect the Apollo 11 astronauts.

In 1951, Erb, a civil engineer, was offered a scholarship to study in the United Kingdom at the College of Aeronautics (now Cranfield University). Believing that humans would one day leave Earth, he did his thesis on heat transfer.

Upon returning to Canada, he went to work at Avro and was one of those scooped up by NASA when the program ended.

Though heat shields had already been used on the Mercury program, it wasn't enough for Apollo, which would be re-entering at the speed of a ballistic missile. Something else to take into consideration was the re-entry angle, which would generate far more heat than the Mercury capsule.

Erb helped develop the ablative heat shield used on Apollo 11's re-entry capsule, covering the bottom of it with a material that burns off when superheated, dissipating the heat. A gassy barrier forms that also insulates the capsule.

Different forms of ablative shields are still used today.

Sudbury as the moon

While this isn't specifically an Apollo 11 fact, it's still part of the Apollo legacy.

Canada may be known as the "Great White North," but ever since the space program began, one region has served as a stand-in for both Mars and the moon.

Once scientists received lunar rock samples from Apollo 11 — the astronauts brought back 21.5 kilograms of it — scientists gained a better understanding of the moon's surface, including impact craters.

And Sudbury, Ont., was a perfect stand-in.

Roughly 1.8 billion years ago, a comet slammed into what today is Sudbury, creating the Sudbury Basin. The region is known for its rich nickel ore, among other metals.

Astronauts were brought to the city to study impact craters and the rock — breccia — that was left behind, similar to what could be found on the moon.

In fact, Sudbury has the honour of being the only Canadian city ever mentioned in the Apollo missions.

"It has a black fracture pattern running right through the middle of it," said John Young during the Apollo 16 geology outing on the moon. "It looks like a Sudbury breccia."

Bonus: Apollo 13

On April 11, 1970, the giant Saturn V rocket blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center with three astronauts — Jim Lovell, John Swigert and Fred Haise — heading toward the moon. The Apollo 13 mission seemed to be going well, with some at mission control saying it was the smoothest ride so far.

But about 56 hours into the flight, an oxygen tank blew up, which, in turn, caused a second one to fail. The three men were roughly 320,000 kilometres from Earth. And then two of the three fuel cells were lost.

With only 15 minutes of power remaining, the astronauts powered down all the systems in the command module and took refuge in the lunar module. Their moon shot was over.

NASA jumped into action to try to get the three men home safely. If they could get back to Earth, one of the many problems facing the astronauts was how they would separate the re-entry capsule from the lander.

Grumman Corporation (today Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems), which designed the lunar module, called upon everyone they could to help, including engineers at the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies (UTIAS), who were asked to perform calculations around the pressure needed to safely separate the two pieces.

In the end, the trio safely returned to Earth on April 17, 1970.