Canadian traditions: Hockey, double doubles ... and video games?

If there was any doubt as to the fundamental difference in mindset between the two sides, Front Page Challenge guest panellist Gary Lautens, a columnist for the Toronto Star, quickly ended it with his first question.

"I'd been led to believe that these games turn your brain to mush, that you turn into some kind of monster," Lautens said. "So do these games really affect kids?"

"Not in the way you are describing," replied Don Mattrick, who along with Jeff Sember created the game, which sold more than 400,000 copies. "They give us a lot of fun and entertainment, but I don't think they have any detrimental effect on our brains."

For the panel of the quiz and current affairs show that was a staple of Canadian television from 1957 to 1995, it was clear that these video games were a curiosity, one that hadn't quite entered their lexicon of what constituted entertainment.

"Have you passed the sales of Trivial Pursuit yet?" Berton asked. "That's the other big Canadian non-electronic game, the kind I understand."

Evolution never did pass Trivial Pursuit, but it wasn't long before video games trumped board games in the world of home entertainment. In Canada, an industry was born.

Billion-dollar boom

If you've played video games in the past decade, chances are you've played at least one made in Canada. Among the heavyweights are Electronic Arts's FIFA Soccer franchises, Edmonton-based BioWare's Star Wars role-playing game Knights of the Old Republic, Ubisoft Montreal's military shooter game Splinter Cell or St. Catharines, Ont.-based Silicon Knights's work as co-developer of the popular stealth game Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes.

And yes, even Trivial Pursuit became a video game in 2004, and yes, it too was made by a Canadian developer, Ottawa-based Artech Studios.

A quarter century after the first Canadian-made video games hit the market, Canada has become home to one of the most thriving video game industries in the world, one that employs 9,000 people in 260 firms, with total annual revenues of between $1.5 billion and $2 billion, according to a 2007 study by the Entertainment Software Association of Canada.

It's also become a linchpin of Canada's efforts to build an information-based economy. As federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty said in 2007: "This kind of innovation, coupled with the highly skilled jobs in this sector, are integral to Canada's future prosperity." In the early 1980s, however, video games weren't the domain of big business, but rather a few entrepreneurs with access to a computer.

Basement businesses

Mattrick is now senior vice-president of Microsoft's interactive entertainment business unit, while Sember is pursuing graduate studies in computer science at the University of British Columbia and recently received a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

But back in 1982, they were just two high-school students who began their business in Sember's basement in Burnaby. After their success selling Evolution through Sydney Development Corp. in 1981, they formed their own game developer company, Distinctive Software Inc., the following year.

Around the same time, 30-year-old programmers Paul Butler and Rick Banks started making video games for a startup Ottawa cable system called Nabu. When Nabu folded, they had their first big hit with B.C.'s Quest for Tires, a game that was based on the then popular caveman comic strip B.C. and that sold more than a million copies.

"We had eight or 10 people and we didn't have any offices," Butler said of the company they formed in the early eighties, then called Artech Digital Entertainment. "We just met at our homes or in restaurants in the Glebe neighbourhood where we lived. There was no outside financing needed because we had so little expenses."

At the time, Butler said, making video games was not easy. There were no art tools, computers ran primitive sound systems — if they had sound at all — and programming involved long hours of entering data before they could see results.

"You'd spend all this time entering in these hexadecimal numbers" — a number in base 16 instead of base 10 — "in the hopes of making a graphic look a certain way, and then you'd run the program and see it had all kinds of errors," Butler recalled.

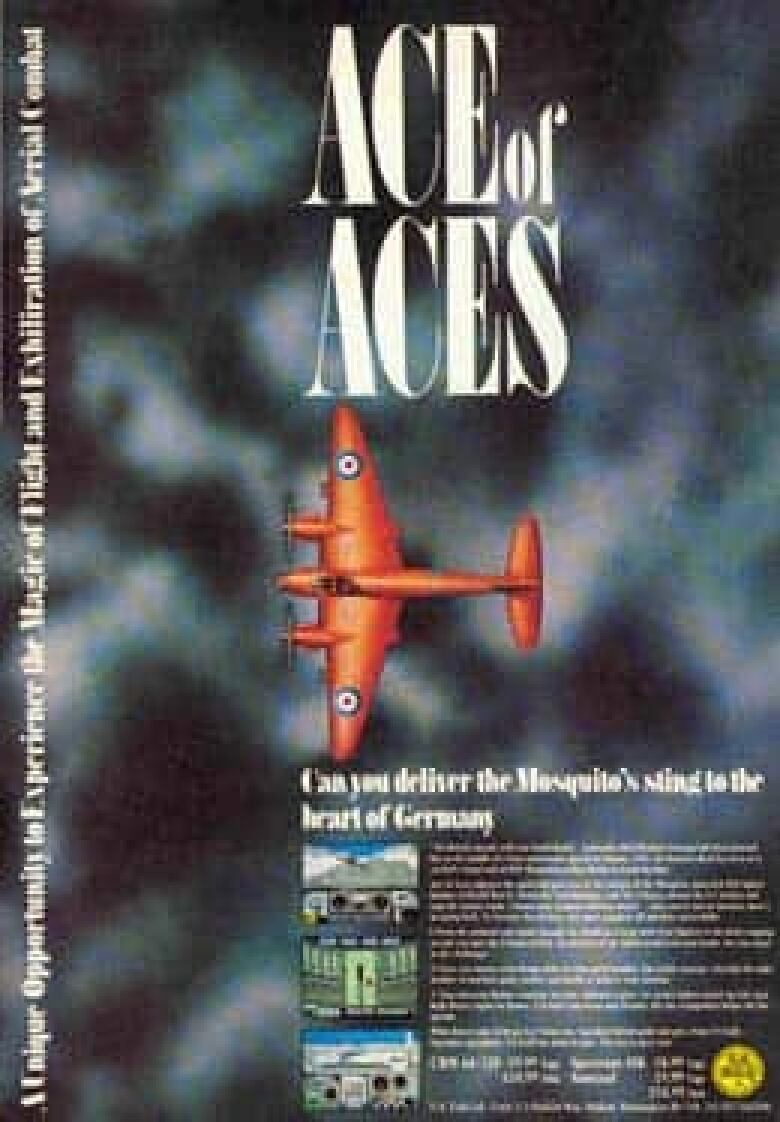

Both companies found work making games for San Jose-based Accolade, games like Distinctive's racing game Test Drive and Artech's warplane game Ace of Aces. As with many games of that era, they were designed to run on early home computers such as the Commodore 64 or consoles such as the Atari 7800. Toronto-based Peter Liepa and Chris Gray were another pair of successful programmers, making the popular Boulder Dash game for a number of platforms in 1984.

Rise of PC opens market in '90s

In 1986, Mattrick bought out Sember at Distinctive, and in 1991 U.S.-based Electronic Arts bought the company and turned it into EA Canada, with Mattrick as its CEO.

EA Canada's arrival coincided with a rash of startups across the country, each primed to take advantage of a couple of trends: the emerging dominance of PCs running Microsoft Windows over the gaggle of systems from companies such as Atari and Commodore, and the arrival in the mid-nineties of a new generation of consoles such as the first Sony Playstation and the Nintendo 64.

Not all of these bare-bones startups survived, but enough did — along with EA and older studios like Artech — to form the backbone of an industry: BioWare, Silicon Knights, Vancouver's Radical Entertainment, Quebec City's Artificial Mind and Movement and London, Ont.-based Digital Extremes are just a few that made a mark after starting up in the early nineties.

Foreign video-game makers, attracted by a skilled workforce and a low dollar, made further investments in Canada, most notably when French software maker Ubisoft opened a studio in Montreal in 1997, but also Rockstar Studios, the makers of the Grand Theft Auto series, who opened one in Vancouver the following year. Meanwhile, other, smaller studios like Relic and Next Level Games, both based in Vancouver; Lunenburg, N.S.-based HB Studios; and Quebec-based Beenox were able to carve out their own niches after starting up around the turn of the century.

Today EA employs about 2,300 in British Columbia and in offices in Montreal and Toronto, while Ubisoft employs about 1,600, making them the two biggest studios in the country, according to the Entertainment Software Association of Canada.

If the early success of Canadian studios was a happy accident, the follow-up investment was a realization on the part of game developers that Canada had a lot to offer, Butler said.

"I think Ubisoft and EA's investment came because they realized it was a good place to do business," he said. "The big difference I think was people; there were great schools producing trained computer students and a critical mass of companies. You just couldn't find that in too many other countries."

Subsequent government and business acceptance of the industry is also a result of familiarity with the medium, said Kelly Zmak, CEO of Vancouver-based Radical Entertainment, the maker of such games as Hulk and Simpsons: Road Rage.

"I think politicians and business leaders have become more accepting because they, unlike the generation before them, grew up with video games and consumed the media," Zmak said.

Industry-wide consolidation

In the last five years, a new trend has emerged, as the sector has moved alongside the rest of the entertainment industry toward consolidation. U.S. developer THQ bought Relic in 2004. Vivendi-owned Sierra Entertainment took over Radical, and Activision bought Beenox in 2005, with both companies now under the ownership of Activision Blizzard after Vivendi and Activision merged earlier this year. Also this year, EA completed its purchase of BioWare.

Artech Studios, which employs about 40 people, has gone in the other direction, with Butler and Banks buying back the company from Astral Media in 2004. Butler said too much consolidation has limited the options for developers.

He cited the Activision Blizzard merger, which eliminated Sierra Online, one of his company's biggest clients. The merger also led the company to lay off 100 employees — or about half the workforce — at Radical in Vancouver.

Zmak, who came to Radical from the U.S. to head up the company in 2005 after Vivendi bought it, said the move was a result of a strategic change at the top levels toward producing fewer, better games.

"It was a hard set of decisions, but we think it will allow us to deliver a better product and make us more competitive," Zmak said.

Consolidation, he said, is a natural process in the industry that first began in Canada when EA first bought Distinctive.

"Whenever companies reach a critical mass, they become inviting to larger companies, but one thing that has always defined the industry is there are low barriers to entry," Zmak said.

"Someone can always come along and start a new company that appeals to a new market, and we've seen that recently with casual games sold on the internet, and we may see that in the future with games on the mobile phone if we can settle on a common platform like we did back with Windows in the 1990s."

It was that early promise of success that attracted Butler to the business.

"Absolutely we saw that video games were going to be big," he said. "The same goes for digital music and high-definition television; I could see that everything was going to be digital and electronic. The only surprise to me was that it took a hell of a lot longer to get there."

"We had to wait for the market to come to us," he said.