In Canada's largest city, a river returns to its roots

Also: Some wildfire evacuees decide never to return home

Hello, Earthlings! This is our weekly newsletter on all things environmental, where we highlight trends and solutions that are moving us to a more sustainable world. Keep up with the latest news on our Climate and Environment page.

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox every Thursday.

This week:

- In Canada's largest city, a river returns to its roots

- The Big Picture: 99.999% of the deep sea remains unseen

- Some Canadians are migrating away from wildfire-prone communities

In Canada's largest city, a river returns to its roots

That's set to change this weekend, with the public opening of part of a $1.4-billion restoration project at Toronto's port lands. Biidaasige Park, part of one of Canada's most ambitious ecological restoration projects, was driven by a push to renaturalize the Don River's mouth as a way to control floods and protect a giant mixed-use redevelopment effort in the area.

"It's really something to celebrate because the river has for so long been in a concrete box," said David O'Hara, manager of park design at the City of Toronto.

"And it's now free again and flowing through the kind of environment that it had flowed through for thousands of years before industrialization changed it."

Biidaasige Park — pronounced Bee-daw-si-geh and meaning "sunlight shining towards us" in Anishinaabemowin — covers about 60 acres and is one of the largest and most complex parks in Toronto. It is on Ookwemin Minising (meaning "place of the black cherry trees"), an island that was newly created by carving out a more naturally meandering outlet for the Don River at the city's waterfront.

The new outlet adds to the existing Keating Channel, which was built at the start of the 20th century. Back then, the Don's natural mouth was filled in, and its waters were diverted into the Keating.

While the Keating was originally enough to contain the flow of water, development and other changes over time made the existing channel inadequate, according to Waterfront Toronto's chief planning and design officer, Chris Glaisek. The new, more natural outlet is actually designed to flood — allowing water to go over its banks and the river to "do what it needs to do without causing too much damage and disruption," he said.

"That's something the original channel was not designed to do. It was designed to simply contain the water — and it's very tough to control nature," Glaisek said.

Without renaturalizing the Don River and creating new ecosystems to absorb rising waters, the port lands and some surrounding neighbourhoods would be flooded during extreme weather events. Climate change is expected to make storms both more frequent and severe, increasing the risk of floods in the city. Planners expect all that land should now be safe from being inundated, and the city plans to build over 14,000 new housing units there.

"It isn't simply about ecology just for ecology's sake, but it's also to create a new type of community that will have a different relationship to nature … a more integrated way of living with nature in an urban environment," Glaisek said.

While flood control is the primary goal of the project, the new river is also bringing species back to the area. Previous analyses have shown that densely populated southern Ontario is an important area for ecological restoration. Restoring natural ecosystems would bring the most benefits for local residents and threatened species by helping provide clean water, drain floods and reduce the severity of heat waves in cities.

"This is certainly a resiliency project, without a doubt, because the risk of these flash floods has only increased with time, with urbanization, with climate change," Glaisek said.

The ecological impacts of the project are already being seen. "We have a few new species of fish that have come back to the harbour that hadn't been seen here in 80 years," Glaisek said. Bald eagles are being spotted there, along with fish like smallmouth bass, bluegill and pumpkinseed.

The park has been planted with native plant species from southern Ontario, including some seeds that were unearthed during the island's construction, like cattail and bulrush that were 100 years old. Many plants important to local Indigenous ceremonies and medicine are also in the park, like sweetgrass, sage and black cherry trees..

A lot of this will be seen for the first time as Torontonians visit the park for its opening celebrations this weekend. But perhaps the most remarkable sight will be the new Don River, flowing more freely into the lake for the first time in over a century.

"It looks like the mouth of the river has been there forever. It really is spectacular," O'Hara said.

—Inayat Singh

Old issues of What on Earth? are here. The CBC News climate page is here.

Check out our podcast and radio show. In one of our newest episodes: The Salinas Grandes in northern Argentina is home to large deposits of lithium, a key mineral in the fight against climate change. But Indigenous leaders in the region say mining the mineral could harm their water supply. We hear how communities are pushing back against potential lithium extraction — and how new mining methods are being tested to find ways of extracting lithium that aren't so damaging to the local environment.

What On Earth drops new podcast episodes every Wednesday and Saturday. You can find them on your favourite podcast app or on demand at CBC Listen. The radio show airs Sundays at 11 a.m., 11:30 a.m. in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Have a compelling personal story about climate change you want to share with CBC News? Pitch a First Person column here.

Check the CBC News Climate Dashboard for live updates on wildfire smoke and active fires across the country. Set your location for information on air quality and to find out how today's temperatures compare to historical trends.

Reader Feedback

Regarding the sustainable cat litter story from two weeks ago, Alma Hyslop of Woodstock, Ont., wrote: "As the owner of two cats, your headline quickly caught my attention, but as I continued to read, my interest quickly turned to horror when I learned that the company that produces litter from flax waste also produces biomass fuel…. Our governments and the biomass industry would like us to believe that it's OK to burn dead plant material instead of fossil fuels, because biomass is renewable. However, 'a molecule of carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere today has the same impact on radiative forcing — its contribution to global warming — whether it comes from fossil fuels millions of years old or biomass grown last year.'"

Write us at whatonearth@cbc.ca. (And feel free to send photos, too!)

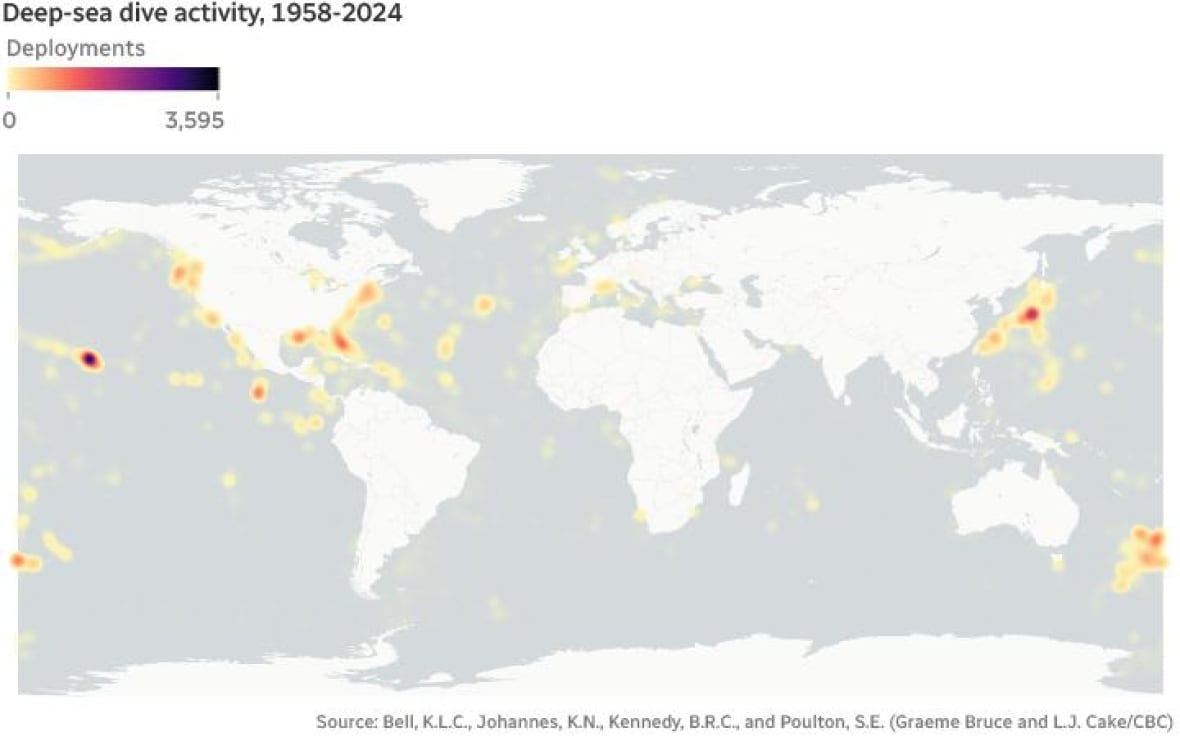

The Big Picture: 99.999% of the deep sea remains unseen

The balloon worm, the bloody-belly comb jelly and the flapjack octopus are among the unusual creatures that thrive in the dark, high-pressure depths of the deep sea. While the deep ocean covers two-thirds of the Earth's surface area, it remains woefully unexplored, with only a "minuscule percentage" mapped, sampled or otherwise observed, according to a recent study published in Science Advances. The researchers plotted 44,000 "deep submergence" activities undertaken since 1958. Those dives identified the first hydrothermal vents on the Galápagos Rift in 1977 and the impact of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill on coral regrowth in the Gulf of Mexico, among other discoveries. And while the number of dives has increased fourfold since the 1960s, they've shifted closer to shore and to waters shallower than 2,000 metres. All told, most deep-sea dives hug the coastlines of the United States, New Zealand and Japan and add up to less than 1,500 square kilometres explored — an area roughly twice the size of Edmonton. What the oceanographic community thinks it knows about the deep ocean is based on a "small and biased" sample that covers a mere 0.001 per cent of the planet, researchers say.

— Hannah Hoag

Hot and bothered: Provocative ideas from around the web

-

The auto industry wants the government to scrap a mandate with targets for selling EVs. An environmental group calculates that doing so would lead to thousands of premature deaths.

-

These Sonoran Desert toads secrete a psychedelic compound from their skin. But that information — combined with habitat loss from climate change — has put the species at risk of extinction, and scientists are trying to adjust their conservation status.

-

India has achieved 50 per cent of its installed electricity capacity from non-fossil fuel sources — five years ahead of its 2030 target under the Paris Agreement.

-

L.A. is no stranger to extravagance, so it tracks that the city will soon also lay claim to the world's largest wildlife crossing. Inspired by a lonely, bachelor mountain lion named P-22, the desert-scaped bridge has been 13 years in the making.

-

Scientists think they may have figured out what's behind a recent surge in global warming. They've traced it to Southeast Asia, mostly China, but say pollution isn't the cause. In fact, it's quite the opposite.

Some Canadians are migrating away from wildfire-prone communities

Michelle Feist never anticipated she would leave Lytton when she moved to the small Interior B.C. village in 2016. For her, it was a fresh start after her husband passed away.

But after a wildfire tore through and destroyed most of the community in 2021, she couldn't bear to return.

"The consequences are lasting. I will never be as I was before the fire," said Feist.

Some residents of Lytton are rebuilding four years after the fire.

Others, like Feist, have chosen to relocate.

Feist initially moved to Williams Lake in the aftermath of the blaze. But she soon realized she was not free from the fire and smoke — and the anxiety— that were present every summer she lived there.

"It changes you."

Feist, a lover of the outdoors, started to dread the upcoming spring and summer seasons. In February, she made the difficult choice to move to a condo in Parksville, on Vancouver Island.

"I just looked at the situation and thought, I don't know if I could do this indefinitely," she said.

Although she misses living in a house, being surrounded by nature and having a garden, she does not regret her decision.

"It's nice to be able to see and breathe, and I'm not dreading the season," Feist said.

"Some disaster could hit it, but it's probably not going to be a wildfire.... I feel safer."

'Difficult decisions'

Feist isn't alone. She says many of her former Lytton neighbours have made the same decision, some even moving out of province.

It's a dilemma that those in wildfire-prone communities are increasingly faced with, says Sarah Kamal, who researches disaster displacement at the University of British Columbia.

"The vulnerability is very real and these communities are having to make some difficult decisions," she said.

Kamal says that due to factors including geography and limited resources, it's not always possible to future-proof a community.

She says that reality is difficult, especially for Indigenous communities that have deep connections to the land.

"If you do leave, you're leaving many, many things — traditional ways of life, community and so on. There's heartache in so many cases."

Displacement unknown

Over 7,000 B.C. residents were temporarily evacuated from their homes during the 2024 wildfire season, according to the B.C. Wildfire Service. That number was in the tens of thousands during the 2023 fire season.

And wildfires in the province are only expected to get worse.

But the number of people who move away long-term due to wildfire risk is difficult to track, says Barbara Roden, mayor of the village of Ashcroft and chair of the Thompson-Nicola Regional District, which has seen numerous evacuation orders and alerts in the past decade.

"People have lots of different reasons for moving into and out of an area."

In recent years, though, she's had more people who are moving to Ashcroft ask her about the wildfire risk and what they need to know.

"That is something that I definitely have seen over the last few years that was [previously] not a factor," said Roden.

"It's something that has to be in the back of our minds."

Farrukh Chishtie, a scientist with the climate migration research group at UBC, says not enough research has been done to look at those who have relocated permanently due to wildfires.

He says climate migration is happening in B.C., but the extent is unknown.

"Where are they going to, and what type of struggles are they facing? We have no data," he said.

The B.C. Wildfire Service confirmed to CBC News the province does not track wildfire migration.

Feist says she feels lucky to have been able to move, as some do not have that option. And she recognizes many people choose to stay in their community.

Although she is happy where she is, she says hardly a day goes by that she doesn't think about fire.

"There's a sense of vigilance that never leaves," she said.

— Michelle Gomez

Thanks for reading. If you have questions, criticisms or story tips, please send them to whatonearth@cbc.ca.

What on Earth? comes straight to your inbox every Thursday.

Editors: Emily Chung and Hannah Hoag | Logo design: Sködt McNalty