'What is it doing to our bodies?': Norfolk residents urge fast action on toxic gas leaks in Ontario county

Geochemist says it's 'by far the largest problem in Ontario' of its kind

Paula Jongerden says she and her neighbours have been living a nightmare for the last decade.

On days when the wind doesn't co-operate, a thick rotten egg-like stench wafts up the valley bordering their Norfolk County properties — a putrid reminder of the inactive and unfiltered wells that have been pumping massive amounts of hydrogen sulfide and methane into the air and water since 2015.

"It's nauseating. Burning eyes, sore throat, like rotten eggs but with a burn to it," Jongerden said.

If it's not the smell that reminds her, it's the otherwise peaceful days that are interrupted by the staccato of distant alarms from a monitoring station that detects high concentrations of toxic gas.

It's a problem locals call the Big Stink and an expert says is the worst of its kind in the province — one Jongerden says needs to be rectified now.

Big Creek, a watercourse that runs through Norfolk County and empties into Lake Erie, has been locked in a struggle with natural gas dating back to 1968. A well that had been open since 1910 was plugged, causing pressure to build and five new wells to erupt before a relief well was drilled to ease the pressure.

In 2015, the Ministry of the Environment ordered that the relief well be plugged, which caused a half-dozen new wells to open up. In 2017, the pressure and higher water levels caused gas to push its way through a layer of clay in the ground, causing it to bubble up through area waterways from newly formed gas springs.

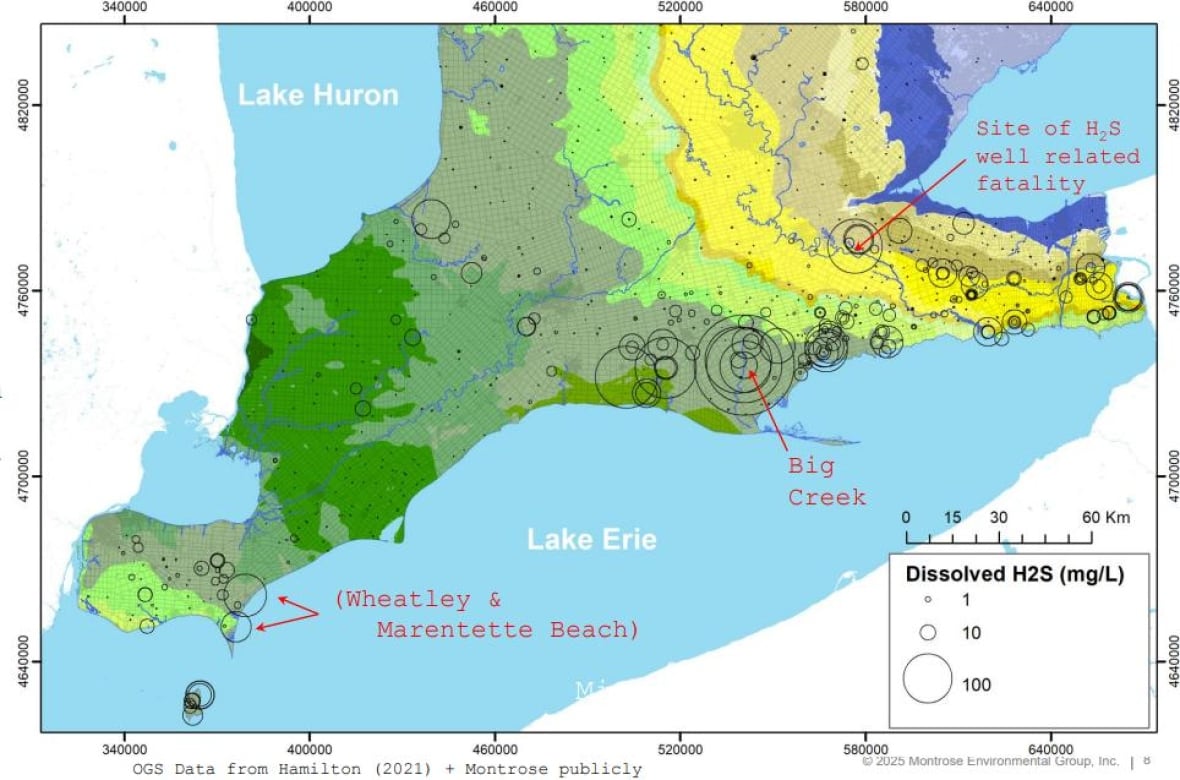

The county used provincial money in 2024 to commission a study from environmental consulting firm Montrose Environmental.

The report was presented to council on July 22 by Montrose geochemist Stewart Hamilton, who said the situation unfolding along Big Creek, especially near Forestry Farm Road where the neighbours live, is "by far the largest problem in Ontario" of its kind.

He said the amount of hydrogen sulfide leaking into the environment from the wells on county-owned land is tens of thousands of times higher than what's legally allowed.

Jongerden said she knew it all along.

"I have metal objects on my property that have turned black because of the corrosion," Jongerden said. "If it's doing that to metal, what is it doing to our bodies?"

She's not the only one affected.

One of the springs that opened in 2017 is a stone's throw away from John Spanjers's home. Water near the creek behind his home is covered in a black film. Sometimes, he said, it can be seen bubbling up to the surface. It smells strongly of rotten eggs, but the smell isn't the main concern.

The longtime resident of the property believes high concentrations of the chemical killed dozens of trees that once stood tall in the marsh behind his home. He also believes it's affected his health directly.

"I've never had headaches. Now I wake up with them frequently. I have been very patient, but my patience is getting very thin," said Spanjers.

But getting politicians to act, especially quickly, has been an uphill battle, the neighbours said.

"The people in our local administration, they will disagree, but I don't think they really care. If they did, something would have happened before now," Spanjers said.

During the last meeting of county council, municipal politicians resolved to urge the provincial government to take the lead in dealing with the issue and paying for the solution. Among the recommendations in the Montrose report are measures like installing a temporary relief well at a cost near $500,000, and installing filters to improve air quality and to treat water, at a price near $1 million.

While municipal politicians seek provincial support for the plan, Spanjers and Jongerden said they believe more urgent action is needed.

"I love Norfolk County. I don't want to be a complainer, but this isn't right," Jongerden said. "Norfolk can afford the $1.5 million to make this right."

Independent MPP and council at odds

Haldimand-Norfolk Independent MPP Bobbi Ann Brady said the wells will be her top priority when provincial politicians return to Queen's Park in October.

"If [these wells] were on private property, it wouldn't have taken 10 years."

Brady accused councillors of "playing politics with a dangerous situation," saying that for the past decade, multiple studies funded by provincial dollars have been done, but the gas still flows just the same.

"Monitoring is good, but it's been ten years. I support this new call to the province, but it's too little, too late," Brady said.

Norfolk Mayor Amy Martin said the county has done what it can by securing over $1 million in provincial funding, much of which went to the recent study and the province's Abandoned Works Program.

She said gas wells are a provincial responsibility that require a response from multiple ministries and residential taxpayers shouldn't have to foot the bill.

"Meanwhile, the Independent MPP has provided no solutions, no technical support — just theatrics at Queen's Park and criticism of her municipal counterparts," Martin wrote in a statement to CBC News.

"That certainly doesn't help the residents of Forestry Farm Road or the taxpayers of Norfolk County but it is an easy position to take when you lack influence."

County bureaucrats say meetings are scheduled with the province in August, and Martin said she will advocate for the issue during the Association of Municipalities of Ontario meeting this month.