Pandemic adds $400M to Muskrat project costs, full power a further 10 months behind

$360 million in bond payments now due, but no revenue is being generated

Nalcor has revealed that delays and complications caused by the pandemic will increase the cost of the Muskrat Falls project by $400 million, confirming earlier projections by the Crown corporation.

The schedule for the project has also encountered more setbacks due to the pandemic and complications with commissioning the powerhouse and the Labrador-Island Link.

As a result, Muskrat will not achieve full power until a year from now, which is 10 months longer than the last scheduled update in January.

These delays are coming at a steep price, with Nalcor announcing that payments of $360 million on the bonds issued to finance the project are also now due to be funded, long before the controversial project begins generating revenue.

Nalcor CEO Stan Marshall said that while total costs related to the pandemic shutdown in March and reduced productivity due to physical distancing measures are roughly $150 million, roughly half of that amount will be covered by the existing capital budget.

But additional financing charges resulting from the delays will drive up the final forecast cost by at least another $300 million.

Marshall spoke with reporters Monday afternoon, and despite the bad news, he pointed out that this is the first actual spike in the project's price tag in three years.

"If you contrast 2017 to current, [there was] very little change," he said. "In fact, if any major megaproject in the world had saw such a small change over a three-year period, they'd be absolutely delighted. It's a remarkable achievement considering the challenges we've had."

Milestone achieved, final commissioning still distant

Nalcor was forced to suspend construction in March after a public health emergency was declared because of the COVID-19 virus.

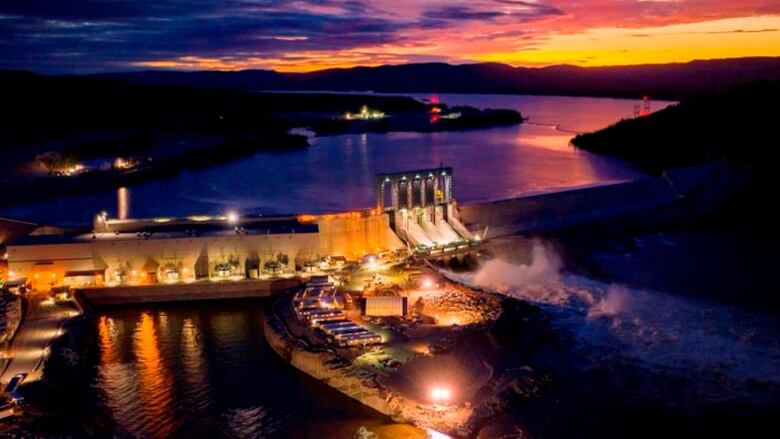

Construction has since resumed, and the project achieved a milestone last Tuesday when first power was completed on the first of four generating turbines, with the unit now linked to the Labrador power grid.

But final commissioning of the project is "to be determined," according to a presentation released by Nalcor.

In another troubling sign, the sychronous condensers at the critical switchyard in Soldiers Pond, where the electricity is converted from direct current to alternating current, are not expected to be ready for operation until August 2021, a full year behind Marshall's last update in January.

The condensers help maintain system stability and keep voltages at specified levels, but have been plagued by binding and vibration issues.

Without the condensers, it's not known whether Muskrat power will be used to displace the Holyrood thermal generating station this winter, but consultants hired to monitor the program have cast serious doubt on that scenario.

On Monday, Marshall said it's possible some Muskrat power could reach the island this winter, but he was not definite.

The software required to operate the 1,100-kilometre power line from Muskrat Falls to the Avalon Peninsula also continues to be hobbled by technical challenges, with Nalcor signalling a final version won't be operational until a year from now.

"We are very pleased with the progress we have made since May," said Marshall. "We still have challenges ahead of us and know people are counting on us. But with the hard work of the thousands of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians working on or supporting the project, we will continue to push hard and achieve our milestones, while keeping one another safe."

It's the latest setback for the Lower Churchill project, which was sanctioned in 2012 at an in-service cost of $7.4 billion.

The project has been dogged by controversy, and came under intense scrutiny during a public inquiry that delivered a scathing report in March that was overshadowed by the pandemic.

Justice Richard LeBlanc called it a "misguided project" and found that the provincial government "failed in its duty to ensure that the best interests of the province's residents were safeguarded."

The inquiry found that the government had "no capacity or strong inclination" to effectively oversee Nalcor, and that Nalcor "exploited this trust by frequently concealing information about the project's costs, schedule and risks."