Federal government assumes control of Clinton Creek remediation in the Yukon

Former asbestos mine near Dawson City closed in 1978 and was later declared abandoned

Almost 50 years after the Clinton Creek asbestos mine in central Yukon was closed, a federal remediation effort at the site is now underway.

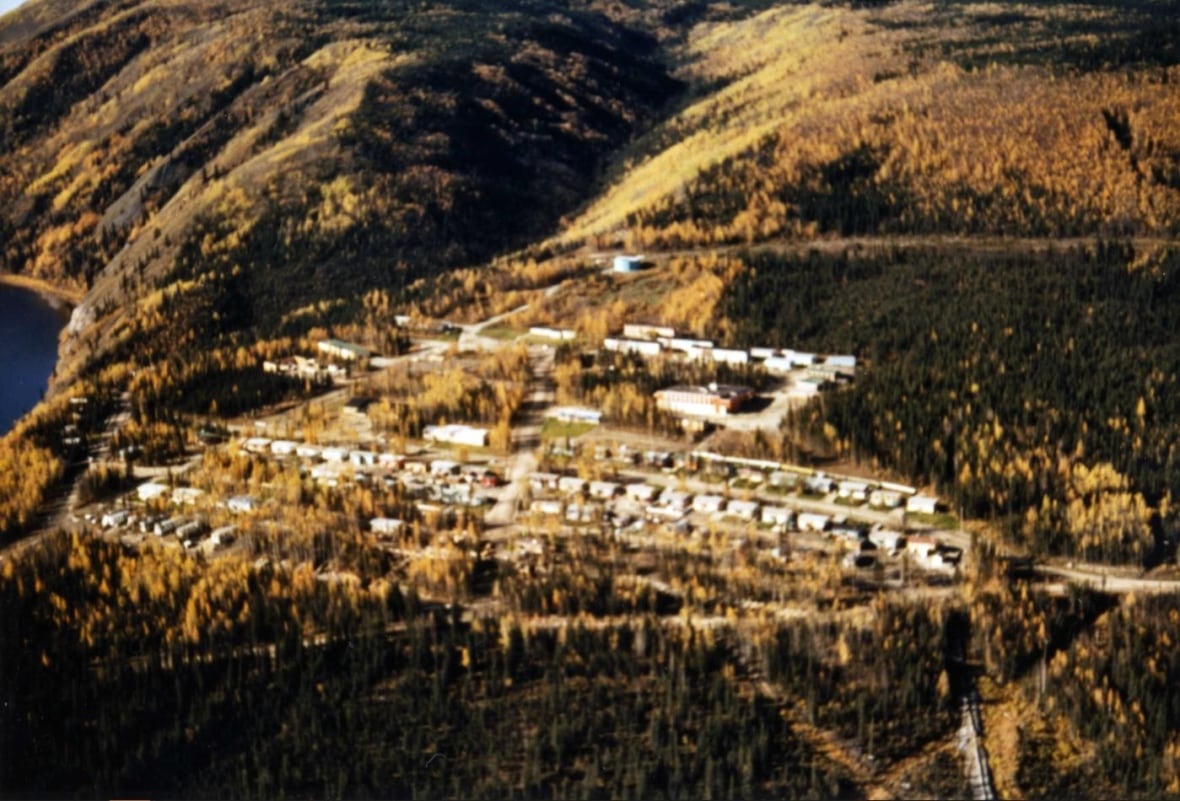

The mine site is located around 65 kilometres from Dawson City, near the confluence of the Yukon and Fortymile rivers. The site is on Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin traditional territory – in Hän, the site is referred to as Ch'ëdä Dëk – and the First Nation is participating in the project.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) recently assumed responsibility for care and maintenance of the site from the Yukon Government, with funding coming from the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program.

The mine was operated by Cassiar Asbestos Corporation Ltd. between 1967 and 1978 and later declared abandoned when the company went bankrupt. While remediation efforts have taken place intermittently by various site owners since then, a CIRNAC spokesperson said the current work at the site represents "a shift toward more comprehensive, long-term remediation planning."

While CIRNAC was unable to provide a timeline for the delivery of a final reclamation plan, the goal is a final closure of the site by 2036.

The remediation work is focused on piles of waste rock and mine tailings left behind in the area. One immediate priority is to deal with a problem dating to the '70s, when a waste rock dump failed, slid, and pinched off Clinton Creek, forming what's called Hudgeon Lake.

"That lake is a big focus of our remediation efforts because it represents a pretty big risk to the area if it were to fail and release a lot of water at once," said Alice McCulley, director of natural resources with Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin.

The possibility of a dam at the lake failing – flooding the creek – is a concern for both Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin and CIRNAC. The First Nation first installed infrastructure to allow safe passage of water, prevent flooding and reduce dam erosion, in the early 2000s.

Now, that infrastructure is reaching the end of its design life.

"Should there be a sort of catastrophic flooding event, the forecasts currently show that there might be impact down to the mouth of Clinton Creek to the Fortymile River," said Martin Guilbeault, environment director for the Yukon with CIRNAC.

Guilbeault says there is significant active monitoring of the site, looking at everything from water flow and water quality to snowpack, in order to inform future planning and understand current risks.

"We know there are few residents [along Fortymile]," he said. "There would be enough time — given the monitoring that's happening — to warn people [of flooding]."

Guilbeault said the risk of a flood isn't huge, but it's still a possibility the government is taking seriously. It's now working to shore up the "dam" – really just a heap of unstable waste rock – and upgrade the existing system that allows water to pass through the Hudgeon Lake.

He said physical stability of the site is another major priority — along with ensuring fish passage through Clinton Creek.

Memories of a ghost town

For a brief moment in the Yukon's history, Clinton Creek was a small but thriving community of around 500 people, boasting a school, a health centre, a tavern, a curling rink and its own newspaper, the Rock Fluff – named after the asbestos the town was built to mine.

It's a period of time Bruce Jones, who spent part of his childhood there, remembers well.

"I remember a lot about the place," said Jones, who now lives on Vancouver Island. "I could almost write a book on my memories.

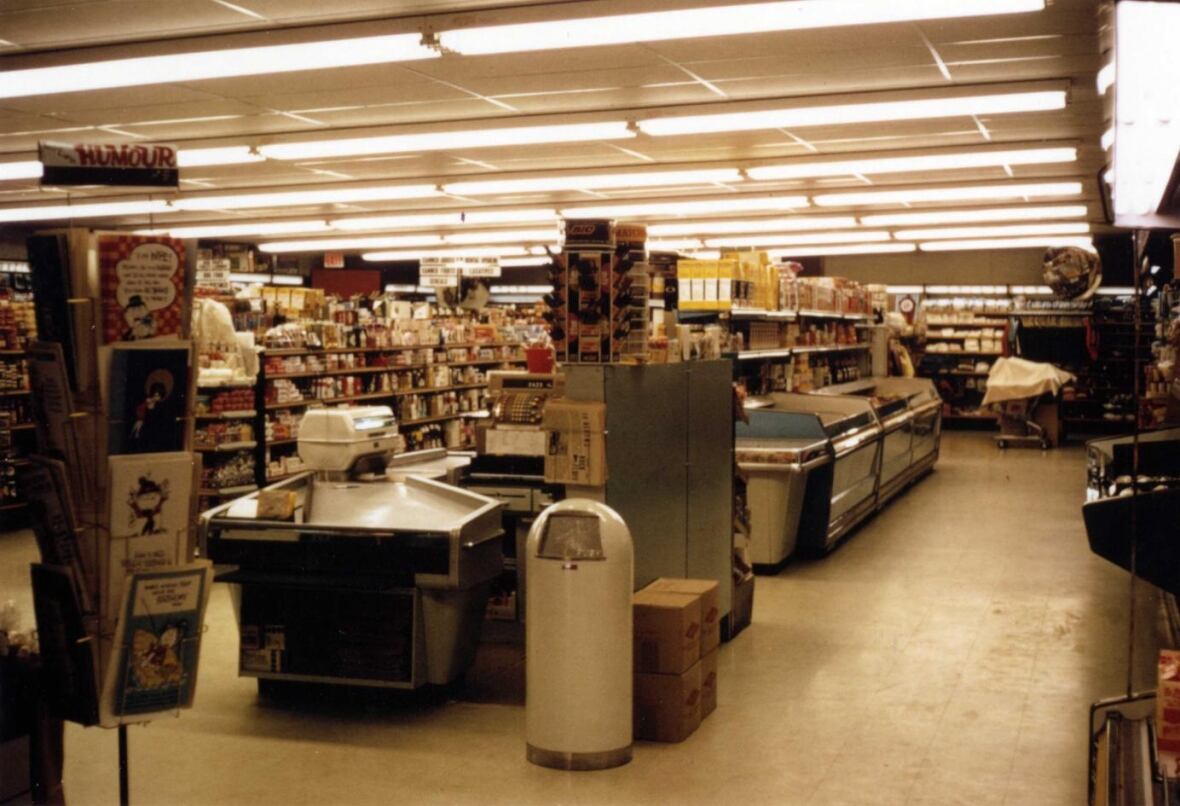

"My father managed the power plant there and my mother worked in the office at the general store," he said. "It was good jobs, and it was a good social atmosphere."

He said his parents also ran the Rock Fluff newspaper.

The townsite and mine was owned by the Cassiar Asbestos Corporation, which also operated in Cassiar, B.C. But unlike former employees and residents of the Cassiar asbestos mine in B.C., Jones says he doesn't worry too much about the impacts of growing up around so much asbestos.

"My mother used to remind me to be conscientious of it, and once in a while you see a full blown newspaper ad warning people about mesothelioma," said Jones, referring to a type of cancer often associated with asbestos exposure. "It can be serious, but I haven't had any repercussions yet."

There is little information available on the long-term health of former employees.

'15 years too late'

McCulley says Clinton Creek was an important fishing site for the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin First Nation long before it became a townsite.

"Clinton Creek is a critically important stream that provides juvenile rearing habitat for chinook salmon," she said. "The juvenile salmon are some of the largest that have been found in the Yukon."

McCulley says prior to the asbestos mine, the stream was able to flow freely from its headwaters down to the Fortymile River, and provided habitat for salmon, grayling, and slimy sculpin along its length.

"Then the landslide blocked off the creek," said McCulley.

Restoring fish passage through the waterway is a top priority for citizens, along with safety measures that will allow access to the site. The First Nation has also directed the government to prioritize citizens and citizen-owned companies for remediation work, to create some economic benefits that can be returned to the community.

In 2017, authors of an oral history project on Clinton Creek, funded by the First Nation and the Yukon and federal governments, attempted to speak with elders to gather cultural knowledge to understand how the land was used before the mine. According to the researchers' final report, elders told them they were "15 years too late" for a traditional land use study, as elders with knowledge of the area were no longer around.

McCulley says the work to stabilize and remediate the site over the past few decades has been slow. She also says it won't be possible to return the land to the way it was before – they're working now to try and improve ecological function.

"There's 50 to 60 years of impact [to the area]," said McCulley. "That's generations of our people and definitely has an impact on our knowledge and use of the area.

"But we certainly hope to reconnect people and rebuild."